Are We in a Recession Yet?

By Thomas F. Siems, Ph.D., CSBS Chief Economist

With the nation’s economic output in 2022 contracting for a second consecutive quarter, the simple rule of thumb for calling it a recession has been satisfied. However, several other economic indicators used to track the nation’s business cycle have not shrunk, including the relatively strong jobs market. So, what is going on? Are we in a recession? What economic indicators should be monitored to know when the economy is in a recession?

The official arbiter for calling U.S. economic recessions is the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER’s) Business Cycle Dating Committee. Their definition of a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.” To gauge economic activity, the NBER Committee examines a range of monthly indicators such as nonfarm payroll employment, real personal income less transfer payments, industrial production, real manufacturing and trade industries sales, employment based on the household survey and real personal consumption expenditures.

The various indicator’s depth, duration, diffusion and directional change are used by the NBER Committee to identify when economic recessions start and end. The start is known as a peak in economic activity, and the end is a trough. To identify the peak (or start of a recession), the NBER Committee examines each of these six economic indicators to see when they contract and that they declined for a sufficient duration or depth.

To make a recession announcement, the NBER Committee does not pre-assign weights to the individual indicators. However, they have said that more influence has been given to nonfarm payroll employment and real personal income less transfer payments in recent decades. These two indicators, along with industrial production and real manufacturing and trade sales, comprise The Conference Board’s Coincident Economic Index (CEI).

By pulling the four CEI components together, this composite index should be an excellent metric to monitor the ups and downs in the U.S. business cycle and to better understand when the next recession will begin, according to the NBER Committee’s official definition.

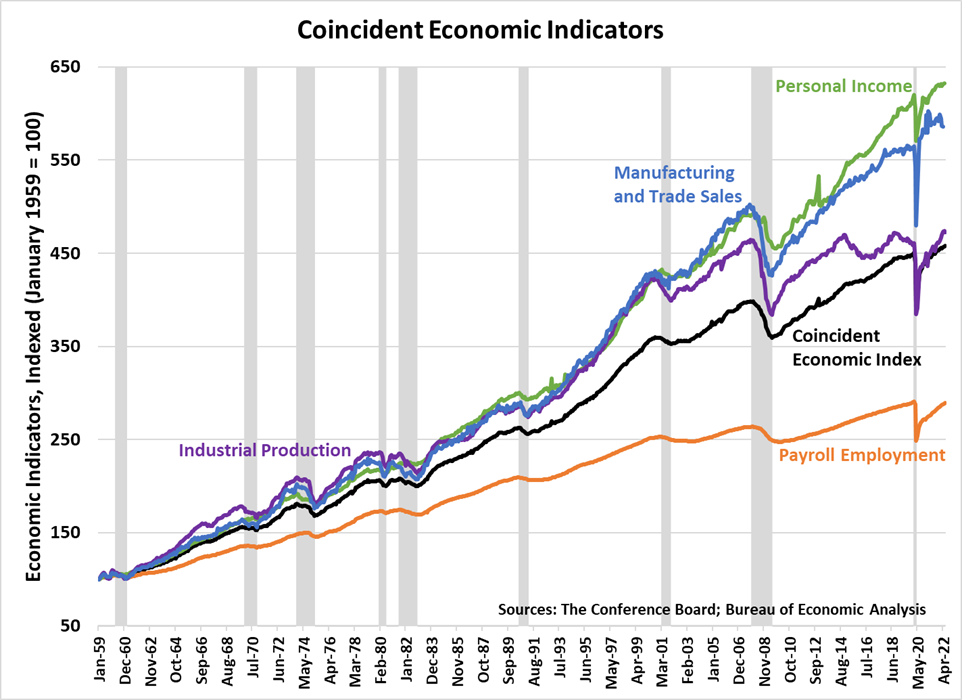

Since 1960, the U.S. economy has experienced nine recessions. Chart 1 shows the CEI and the four economic components that comprise it, where all the metrics are indexed to January 1959. The nine recessions are delineated by the grey shaded bars.

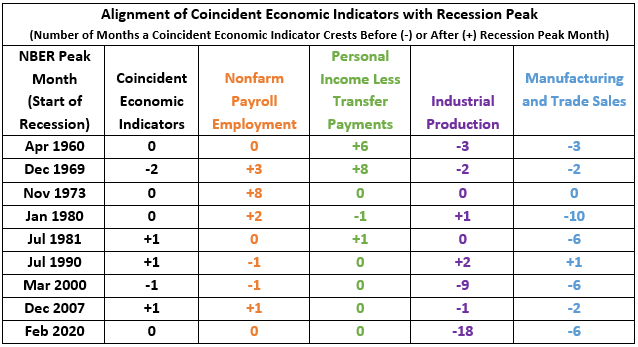

The chart shows that each coincident indicator crests near the peak month of each official recession. To take a closer look, the following table shows how closely each economic indicator aligns with the peak month that marks the beginning of each recession. For example, a minus one (-1) signifies that the given economic index peaked one month before the recession’s official peak as determined by the NBER Committee.

The table shows that the CEI has correctly signaled the starting month of four of the last nine recessions and was off by just one or two months in identifying the onset of the other five. Moreover, for the last five recessions (since the 1981 recession), payroll employment and personal income less transfer payments have proven to be the two best-aligned economic series that make up the CEI.

So, what are these indicators telling us now?

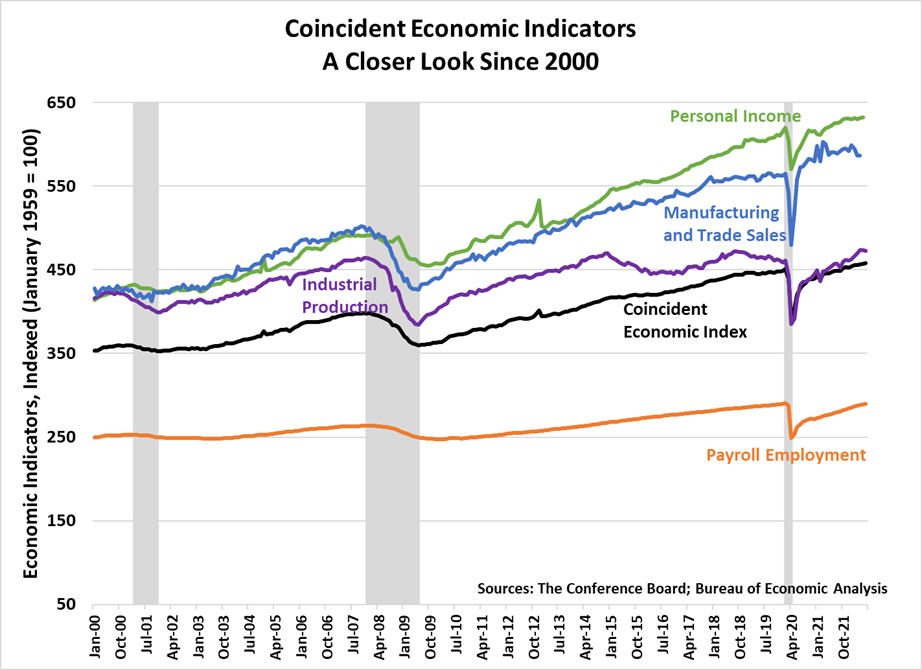

Chart 2 shows that three economic indicators (CEI, nonfarm payroll employment, and personal income less transfer payments) have continued their upward trajectory based on data through June 2022. That is, there is no evidence yet from these coincident measures that the economy has reached a summit and another recession has commenced.

But, with the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ recent announcement that real gross domestic product (GDP)―the inflation-adjusted value of the nation’s final output of goods and services―contracted for the second consecutive quarter, this is certainly paradoxical.

Could this be the first “full employment” economic contraction in modern U.S. history?

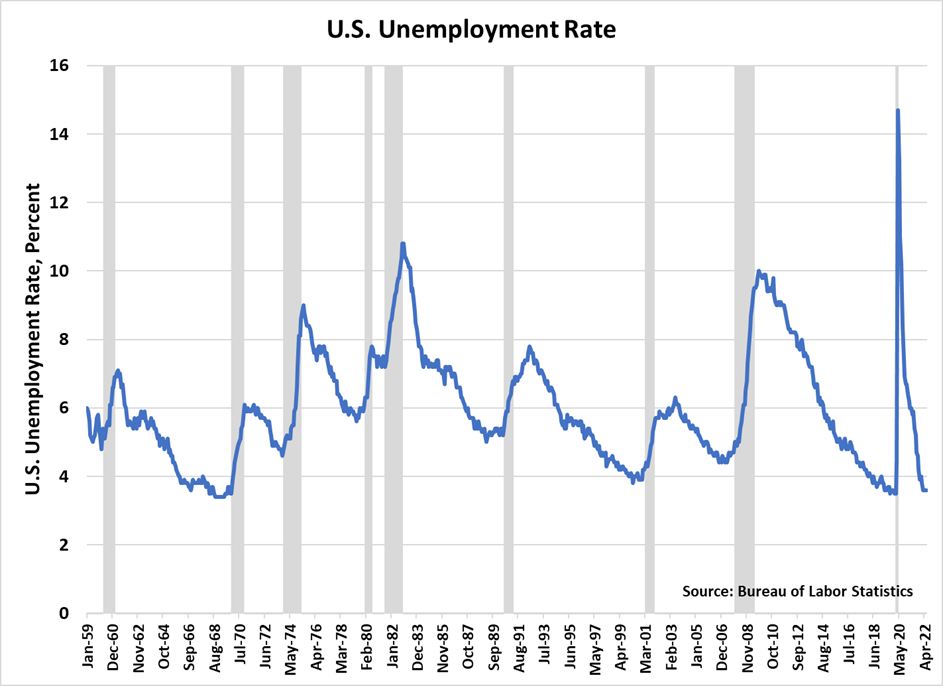

Real GDP contracted 1.6% in the first quarter and another 0.9% in the second quarter, yet the nation’s unemployment rate has remained at a near-record low of 3.6% since March 2022. Moreover, job growth has continued to advance by more than 500,000 per month on average over the past year and the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) continues to show more than 11 million jobs available, roughly twice the level from just two years ago.

Could this be the first “full employment” economic contraction in modern U.S. history?

Chart 3 shows how the U.S. unemployment rate has behaved across the nine recessions since 1960. In every case, the unemployment rate hit a cyclical low just before the start of a recession and then increased by an average of 4.1 percentage points before starting to decline again. In other words, the United States has never had a recession without significant job losses and a simultaneous increase in the unemployment rate.

So far, the strength of the labor market has kept the U.S. economy out of a recession. But there is clearly something else going on right now that has negatively impacted economic growth.

With inflation surging, consumer and business confidence have dropped to record lows. The Federal Reserve’s enormous monetary stimulus over the past two-and-a-half years has doubled the size of its balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion. Add to that roughly $6 trillion in rapid federal government spending during the same period and it is no wonder we have high inflation and stagnate economic growth. This is the definition of stagflation.

Right now, the Federal Reserve’s ability to effectively engineer a soft-landing and avoid a recession is arguably the main unanswered economic question. The Federal Reserve continues to aggressively raise interest rates to cool-off demand and tame additional price increases, but the excessive monetary stimulus put into the economy over the past 30 months might be too much to overcome quickly.

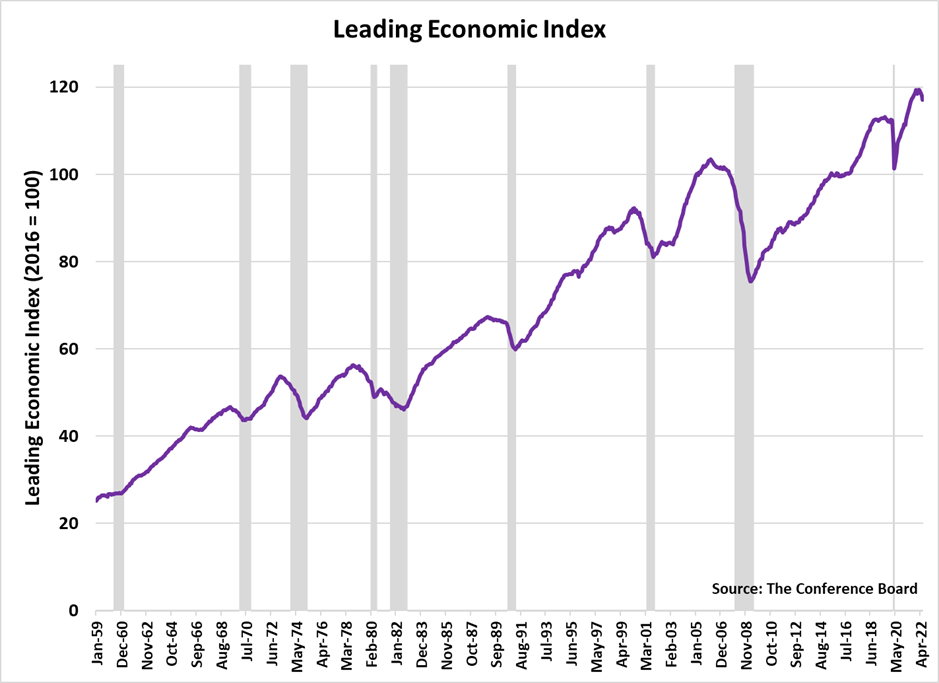

Indeed, the risk of a recession is rising, as evidenced by The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index (LEI) comprised of ten economic measures that together provide an advanced look at where the economy is likely headed. Components of the index include financial indicators (stock prices, interest rate spreads, credit conditions), confidence indicators (consumer expectations, various new orders indexes, building permits), and labor market indicators (hours worked, initial claims for unemployment insurance).

As shown in Chart 4, the LEI peaked prior to each recession, anticipating the start of each downturn by at least eight months. Except for the 2020 pandemic/lockdown-induced recession, all previous recessions were preceded by at least four monthly declines in the LEI. Ominously, the index peaked in February 2022 and has fallen each of the last four months, prompting The Conference Board to report that “a U.S. recession around the end of this year and early next is now likely.”

In summary, an examination of all these economic indicators leads me to believe that the U.S. economy is not in a recession now (July 2022), but that we are headed toward one soon as we wallow through stagflation. And that leads to the next question: How bad will the next recession be?

The Dr. Doom in me worries about persistent and higher inflation, more fiscal and monetary policy missteps, mounting geopolitical tensions, ongoing severely constrained supply chains, tighter credit conditions and further belt-tightening by both consumers and businesses.

The Dr. Boom in me hopes that the Fed can choke off inflation enough to reignite consumer and business confidence and that jobs and real personal incomes continue to advance at a steady pace.

For evidence on how the economy continues to evolve, I plan to keep a close eye on The Conference Board’s Coincident and Leading Economic Indices, as well as inflation rates, labor market conditions and the Federal Reserve’s policy decisions.

Get Updates

Subscribe to CSBS

Stay up to date with the CSBS newsletter

News to your ears,

New every month.CSBS Podcasts