Spotlight - Recent Trends in Commercial & Industrial Lending

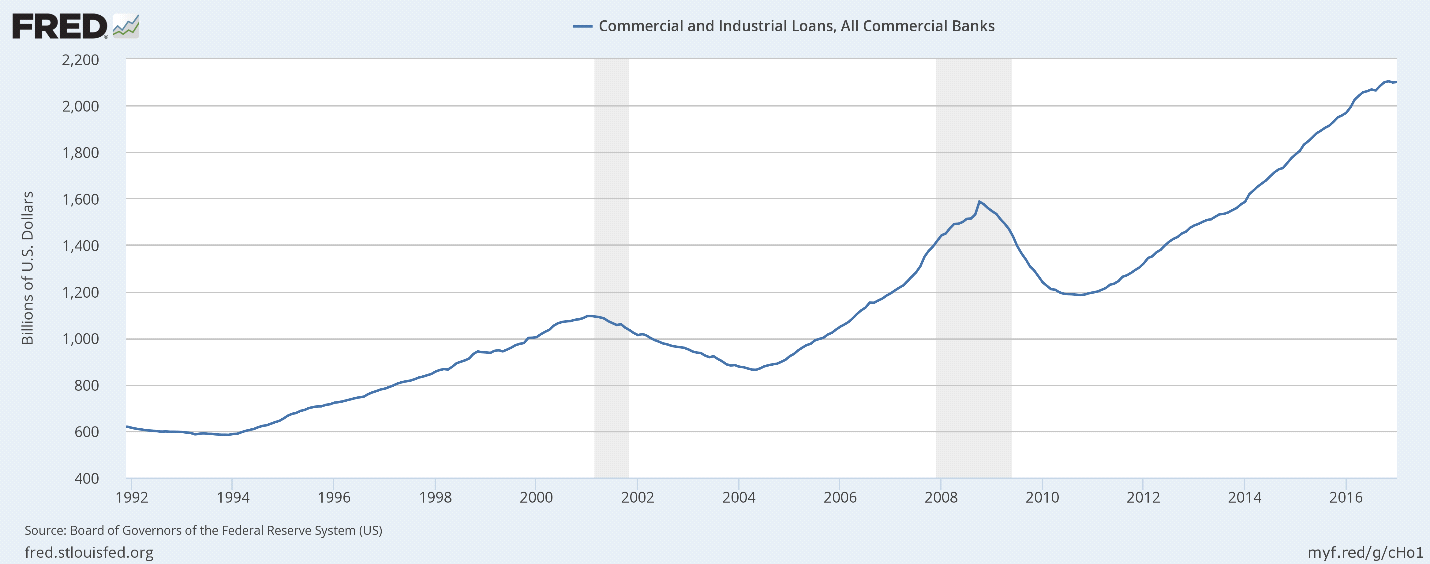

Commercial and Industrial (C&I) lending is at an all-time high, with nearly $2.1 trillion in loans to businesses currently on the books of US commercial banks. After taking a hit following the financial crisis, the aggregate level of commercial lending has increased by more than 35% since 2010.[1]

|

Key Findings

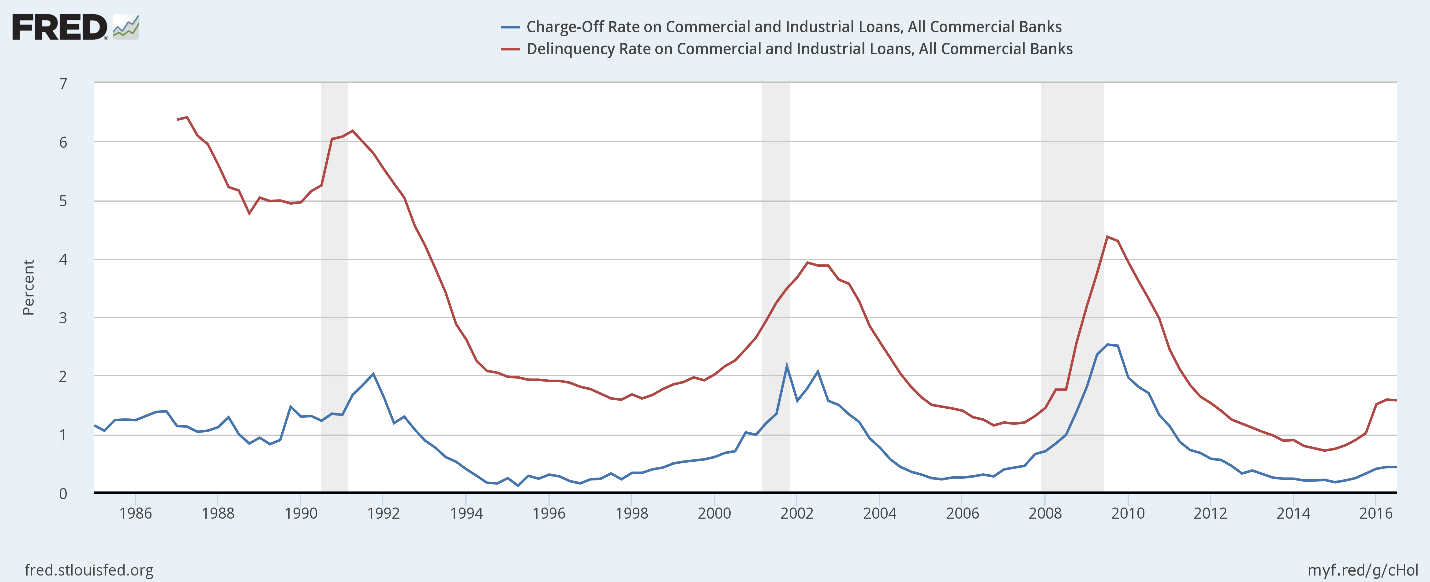

This significant growth can be attributed to a number of factors, including historically low interest rates, improving economic conditions, and until recently, low default rates. |

Senior loan officers surveyed by the Federal Reserve have reported strong (but slowing) demand for commercial loans over the past few years, and it is likely that many bankers who weathered the crisis decided that providing commercial loans for working capital or other business purposes was less risky than speculative commercial real estate lending.

Both rapid growth and increasing delinquencies have caused C&I lending to become an area of increasing concern for regulators and bankers.

What are Commercial and Industrial Loans?

Commercial and Industrial loans, also referred to as business or commercial loans, include loans made to businesses, corporations, or individuals for commercial, industrial, or professional purposes. The C&I definition excludes loans made to finance commercial real estate, agricultural loans, and loans to individuals that are not for business purposes.

Businesses in all sectors of the economy seek commercial loans to provide working capital or credit for numerous purposes ranging from investments in equipment to inventory financing.

C&I loans do not come in one-size fits all packages, and they differ significantly in structure, pricing, and monitoring practices.

Despite the customized nature of this type of lending, commercial loans generally share certain characteristics. Terms for most commercial loans are generally much shorter than loans involving real estate, and they are almost always backed by assets of the operation.

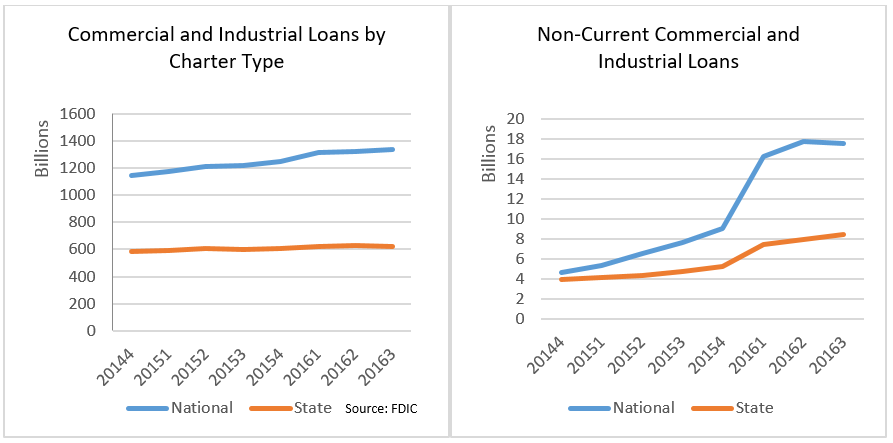

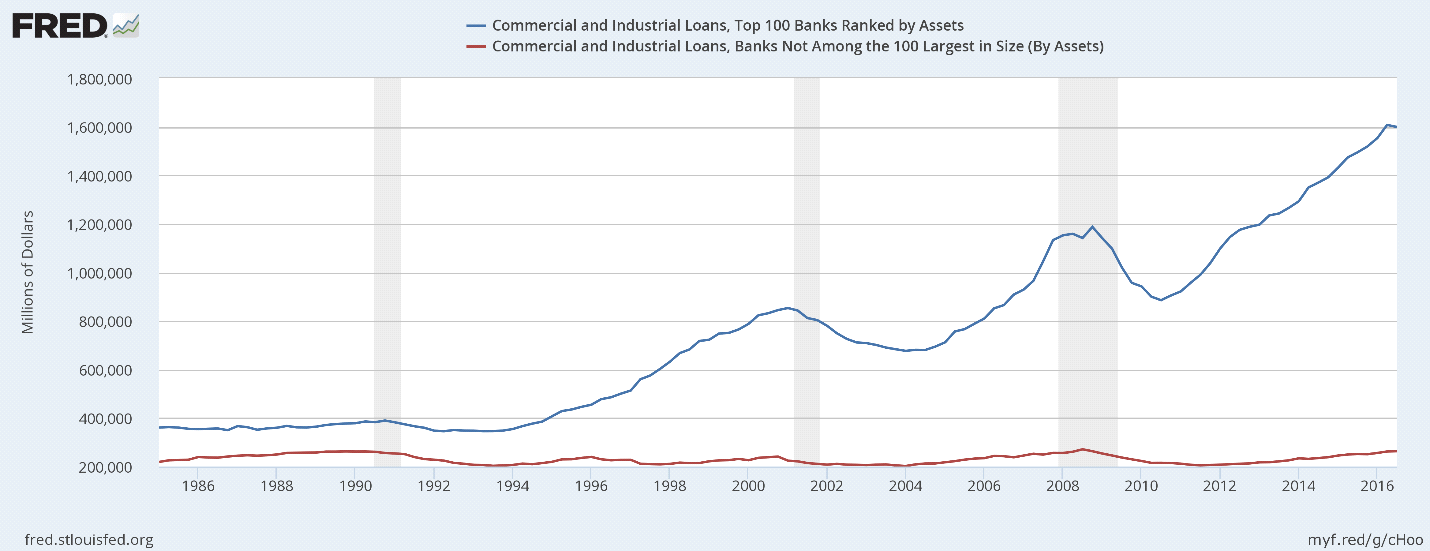

The market for C&I loans is currently dominated by larger banks. National banks accounted for nearly 70% of existing C&I loans as of Q3 2016, with 39% of the industry total coming from the four largest national banks — JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and Citibank.[2]However, community banks provide a significant amount of the nation’s small business lending, much of which is included in the C&I definition.

C&I loans accounted for 21.3% of the industry’s net loans and leases as of third quarter 2016. Out of all loan types, C&I lending was outpaced only by 1-4 family residential mortgages, which accounted for 21.8% of total net loans and leases. The FDIC’s Third Quarter 2016 Quarterly Banking Profilenoted that FDIC insured banks increased C&I lending by 7.8% over the past year.

The third quarter saw total non-current loans and leases decline for the 25th time in the past 26 quarters, reaching the lowest levels since year-end 2007. While most loan categories saw improved performance, non-current C&I loans increased for the seventh consecutive quarter to 1.34% of all C&I loans industry-wide.

A large volume of C&I loans moved from past-due to non-performing in 2016. Net loan losses for the industry increased for the fourth consecutive quarter in the third quarter (16.9% year over year). The increase was driven almost entirely by nearly $1 billion in net charge-offs for C&I loans, a 82.7% increase from a year prior.

Industry net income suffered early in the year due to the losses. The first quarter’s 2% decrease in quarterly earnings was the first quarter’s first decline in two years. Despite the losses in this segment, the industry as a whole has performed strongly in 2016, with a 12.9% increase in net income compared to the third quarter of 2015.

While the industry grew their aggregate portfolio of C&I loans by nearly 8%, community banks increased C&I balances by only 1.2% over the previous 12 months. C&I loans to small businesses declined by .5% at community banks in the third quarter.

The decreased commercial lending activity seen at community banks could be the result of tightened underwriting standards and/or decreased demand for commercial lending. However, multiple members of the CSBS Risk Identification Team have reported a more accommodative banking environment for C&I lending. This is especially true in the Upper Midwest/Great Lakes region, where this loan segment is seeing stronger growth.

Despite the limited new activity in commercial lending, community banks are not immune from losses on existing C&I loans. As of the third quarter, every major loan category at community banks had lower non-current rates compared to the previous quarter except for C&I loans, which increased by 1 basis point.[3]

What is Driving C&I Delinquencies?

Following the Great Recession, the US energy sector experienced a rapid expansion due to high energy prices and the increased application of new extraction technologies (hydraulic fracturing) that increased the speed of production for the industry. This boom was short-lived, however, and the U.S. has seen a sustained decline in energy prices since 2014.

Low prices have resulted in layoffs, lower profits, and increasing debt for oil and gas companies operating in the U.S.[4]

Since the start of the downturn in 2014, as many as 220 energy related companies have declared bankruptcy. Oil and gas companies defaulted on $39 billion in high-yield energy debt in 2016, and the high yield bond default rate for the energy sector peaked at 18.8% during the year.[5]

The downturn in the industry has been the main driver of increasing commercial loan delinquencies, and regions with significant exposure to the energy sector have been hit particularly hard.[6]

The negative impact of low oil prices is not limited to commercial lending. Commercial real estate has also suffered in exposed areas as vacancy rates on newly built hotels, apartment buildings, and offices have increased significantly.

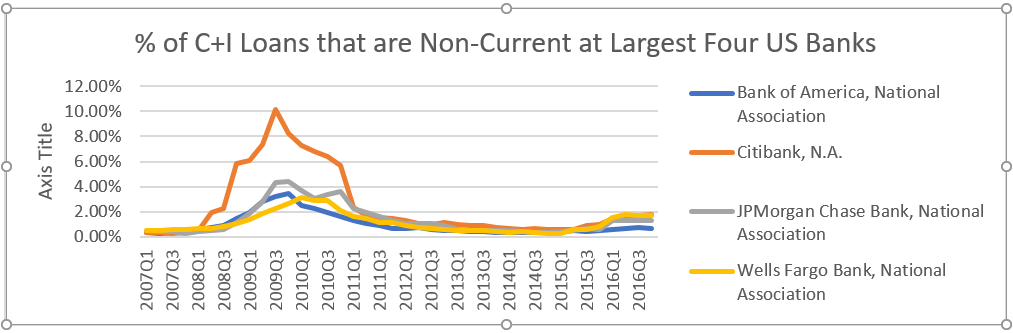

Losses have been concentrated in the largest national banks that made significant investments in the energy sector. As of the middle of 2016, large banks had more than $140 billion in unfunded credit lines to energy companies.[7] As conditions have deteriorated and bankruptcies mount, the risk of borrower default has increased.

In response to the rising delinquencies and charge-offs, the banking industry increased loan loss provisions by $3.6 billion in 2016. Bank of America added $997 million to their provision for loan and lease losses, noting serious issues within their $22 billion energy portfolio.

In April 2016, JP Morgan noted that they were increasing their provision by 88% in response to losses within their oil, natural gas, and pipeline businesses. The move by the nation’s largest bank resulted in the company’s first decrease in profits since the end of 2014.

Also, Wells Fargo made a significant increase in their reserves. The increase by the bank was their first provision increase since 2009 and it was tied directly to stress and deterioration in the oil and gas sector.[8]Wells Fargo is especially exposed due to the fact that many of its loans were made to companies with poor credit ratings. As of second quarter 2016, the company was monitoring $1.9 billion of nonperforming oil and gas loans, an increase of 72% since year-end 2015.[9]

Additional Drivers of C&I Delinquencies

Trouble in the energy sector is not the only driver of commercial loan delinquencies.

Overall corporate profitability is below normal, with S&P 500 company earnings totaling well below levels seen in recent years.[10]

The storefront retail industry is struggling as online retail continues to gain market share. Brands including Sears, JC Penney’s, Barnes & Noble, Abercrombie, and Radio Shack have all struggled to compete with online retailers.

Malls are also experiencing difficulty across the United States. Analysts have predicted that 15% of US malls will fail or be used for non-retail purposes in the next 10 years.[11]

Sears and other companies have sought credit from hedge funds and other non-bank sources as banks have sought to limit their exposure to the big-box retail sector.

Niche markets have also experienced difficulty. For example, Wells Fargo has the largest presence of any bank in Alaska. Bad salmon seasons, an aging fishing fleet, and low international pricing have all contributed to a poor outlook for the Alaskan commercial fishing sector, and Wells Fargo has responded by reducing their involvement in this specialized type of commercial lending.[12]

While niche lending can be profitable for banks, the many factors at play emphasize that banks must build significant expertise in these unique markets in order to adequately monitor risk within their loan portfolios. Thus, it can be difficult for new lenders to enter niche markets.

How are Banks Thinking About C&I?

he results of the Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer survey indicate that banks are reducing their risk tolerances and tightening their underwriting standards on commercial and industrial loans.

The tightening is most prevalent for loans made to large and middle-market firms.

Banks are also restructuring outstanding loans, requiring additional collateral, and setting aside additional reserves as described above.

Survey respondents also said that some banks are hedging the risks arising from declines in energy prices through derivatives contracts, and enforcing material adverse change clauses to limit the ability of firms to draw on existing credit lines.

October 2016 survey respondents reported that C&I loan demand is decreasing moderately. It was noted that that customers may be shifting their commercial borrowing demand to other sources of funding as non-bank lenders compete for commercial customers.[13]

As challenges within the energy sector persist, banks are showing increased interest in the industrial side of C&I lending. Manufacturing is a capital-intensive business sector that has been performing well in the US. Banks are able to engage in this sector in multiple ways. In addition to providing loans and financing, banks are providing account receivable services, cash flow management, factoring, and tax assistance.[14]

Outlook

Despite the large numbers of delinquent commercial loans, it is important to note that loans to oil and gas companies are estimated to account for no more than 5% of the industry’s total outstanding commercial loans.[15] No comparison can be made to 2007 when mortgage loans accounted for a much larger portion of bank assets. It is also not expected that the downturn in the energy industry will result in a replay of the events seen in the 1980’s when 9 out of the 10 largest banks in Texas failed, along with many others.[16] This is in part due to the fact that today’s banks are much more geographically diversified than in the past.

The FDIC’s problem bank list continues to decrease, and there have been no failures of energy dependent banking institutions in recent years.

As oil prices begin to rebound, it is possible that the worst is over for the energy industry and its lenders. Fitch Ratings has projected that US energy defaults will decrease next year, and they have forecasted a high-yield default rate for 2017 of only 3% compared to 2016’s high point of 18.8%.[17]

However, problems could worsen within the retail sector. Fitch recently increased the sector’s projected default rate from 1% to 9% citing increased online competition for retailers and changing consumer spending behavior.[18]

Overall, banks appear to be successfully mitigating the impact of low energy prices and the broader downturn in commercial lending. However, continued monitoring of the effects on the banking sector is necessary to ensure that local communities can access credit for commercial purposes.

Cited Sources & Additional Resources:

FDIC Financial Institution Letter 49-2016. “Prudent Risk Management of Oil and Gas Exposures.”

Cited Sources

[1] Federal Reserve Economic Data, FRED. Accessed here: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

[2] FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile, Q3 2016

[3] Call Report Data, Accessed via FDIC Statistics on Depository Institutions: https://www.fdic.gov/bank/statistical/

[4] Liberty Street Economics Blog. “Are Banks Being Roiled By Oil?” James Vickery, Lauren Thomas, and Ulysses Velasquez. October 24, 2016. Accessed here: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/10/are-banks-being-roiled-by-oil.html

[5] “The End of the Oil and Gas Bankruptcy Wave.” Oil Price.Com. Charles Kennedy, December 29, 2016. Accessed here: http://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/The-End-Of-The-Oil-And-Gas-Bankruptcy-Wave.html

[6] “FDIC Quarterly: C&I Loan Delinquencies Tick Higher.” Wells Fargo Securities Interest Rate Weekly. John Silva and Michael Pugliese, October 19, 2016. Accessed here: https://externalcontent.blob.core.windows.net/pdfs/irwk-19.pdf

[7] Liberty Street Economics Blog. “Are Banks Being Roiled By Oil?”

[8] “Toxic Oil Loans Create Trouble for Big Banks.” CNN Money. Matt Egan. April 14, 2016. Accessed here: http://money.cnn.com/2016/04/14/investing/oil-banks-bank-of-america-wells-fargo/?iid=EL

[9] “Why Bankers are Wary of Office, Hotel Loans—and Bullish on Manufacturing.” National Mortgage News. Andy Peters. January 6, 2017. Accessed here: http://www.nationalmortgagenews.com/news/servicing/why-bankers-are-wary-of-office-hotel-loans-and-bullish-on-manufacturing-1094290-1.html

[10] “Loan Delinquencies Signal for Caution.” Seeking Alpha. June 10, 2016. Accessed here: http://seekingalpha.com/article/3981310-loan-delinquencies-signal-caution?page=2

[11] “America’s Shopping Malls are Dying a Slow, Ugly Death.” Business Insider. Hayley Peterson. January 31, 2014. Accessed here: http://www.businessinsider.com/shopping-malls-are-going-extinct-2014-1

[12] “Wells Fargo Looks for Positives, and a Budget Plan from Juneau.” Alaska Journal of Commerce. DJ Summers, February 1, 2017. Accessed here: http://www.alaskajournal.com/2017-02-01/wells-fargo-looks-positives-and-budget-plan-juneau#.WKSyB0c1S4F

[13] Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. April 2016, July 2016, October 2016, and January 2017. Accessed here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/SnloanSurvey/

[14] “How Banks Drive Growth in American Manufacturing.” ABA Banking Journal. Evan Sparks, October 6, 2016. Accessed here: http://bankingjournal.aba.com/2016/10/how-banks-drive-growth-in-american-manufacturing/

[15] Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. April 2016

[16] “Don’t Forget the 1980’s.” AEI. Alex Pollock, March 31, 2015. Accessed here: http://www.aei.org/publication/dont-forget-the-1980s/

[17] “Fitch: US HY Default Rate Forecast at 3%, Energy to 3% in 2017.” Fitch Ratings. December 15, 2016. Accessed here: https://www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/1016547

[18] Ibid