Too Small to Scale: What 10 Years of Data Say About Community Bank Compliance Costs

By CSBS Chief Economist Thomas F. Siems and CSBS Vice President for Policy Nathan Ross

For years, community bankers have warned that the growing thicket of federal regulations is suffocating smaller institutions. The compounding effect of these rules lands hardest on the banks least able to absorb them. The refrain has become familiar: small community banks don’t have armies of compliance officers or sprawling technology budgets; yet they face regulatory mandates often meant for larger institutions. Most of that argument rested on anecdotes and intuition rather than solid, quantitative evidence. But now, drawing on an unusually rich dataset—a decade’s worth of information from the CSBS Annual Survey of Community Banks, covering 2015 through 2024—we have statistically significant evidence behind the claim that regulation weighs more heavily on the smallest banks. And the empirical findings are hard to ignore.

How the CSBS Community Bank Survey Measures Compliance Burden

In each annual survey, hundreds of community bankers estimate how much of their operating costs go toward compliance—broken down into categories such as personnel, data processing, legal, accounting and auditing, and consulting. Responses to the banks’ financial statements were then matched to the surveyed banks and then grouped into asset-size quartiles to see how the burden scales. The research question being asked is deceptively simple: are smaller banks devoting a greater share of their resources to compliance than their larger peers? And if so, how large—and how consistent—is that gap?

Smaller Banks Consistently Spend a Higher Share on Compliance

The short answer to the first question is an emphatic yes. Across 10 years of data, four of the five expense categories show that smaller community banks shoulder a markedly higher proportion of compliance costs. The answer to the second question is that the differences are significantly large and consistent across all years for four of the five expense categories.

Which Cost Categories Show the Biggest Gaps?

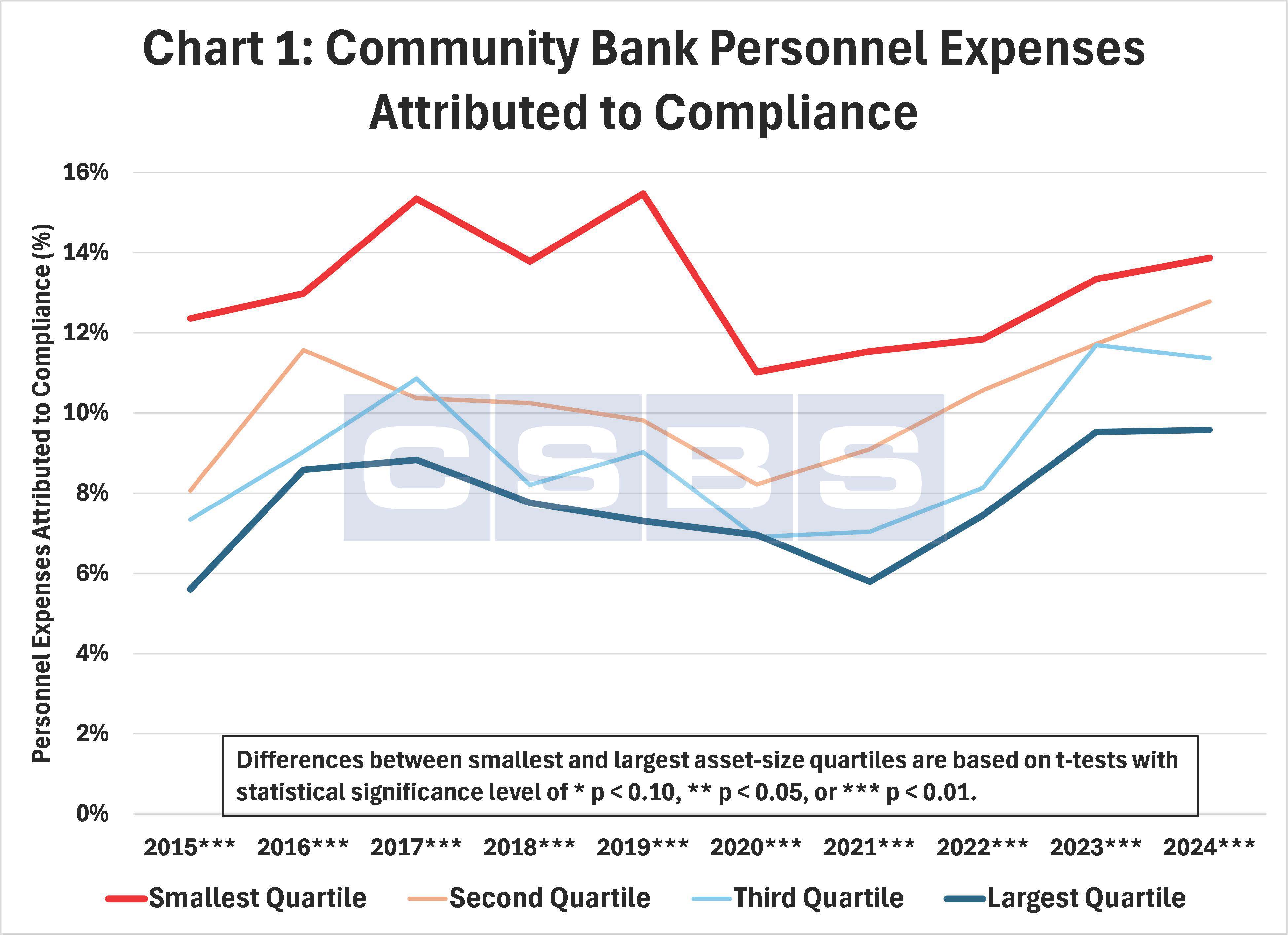

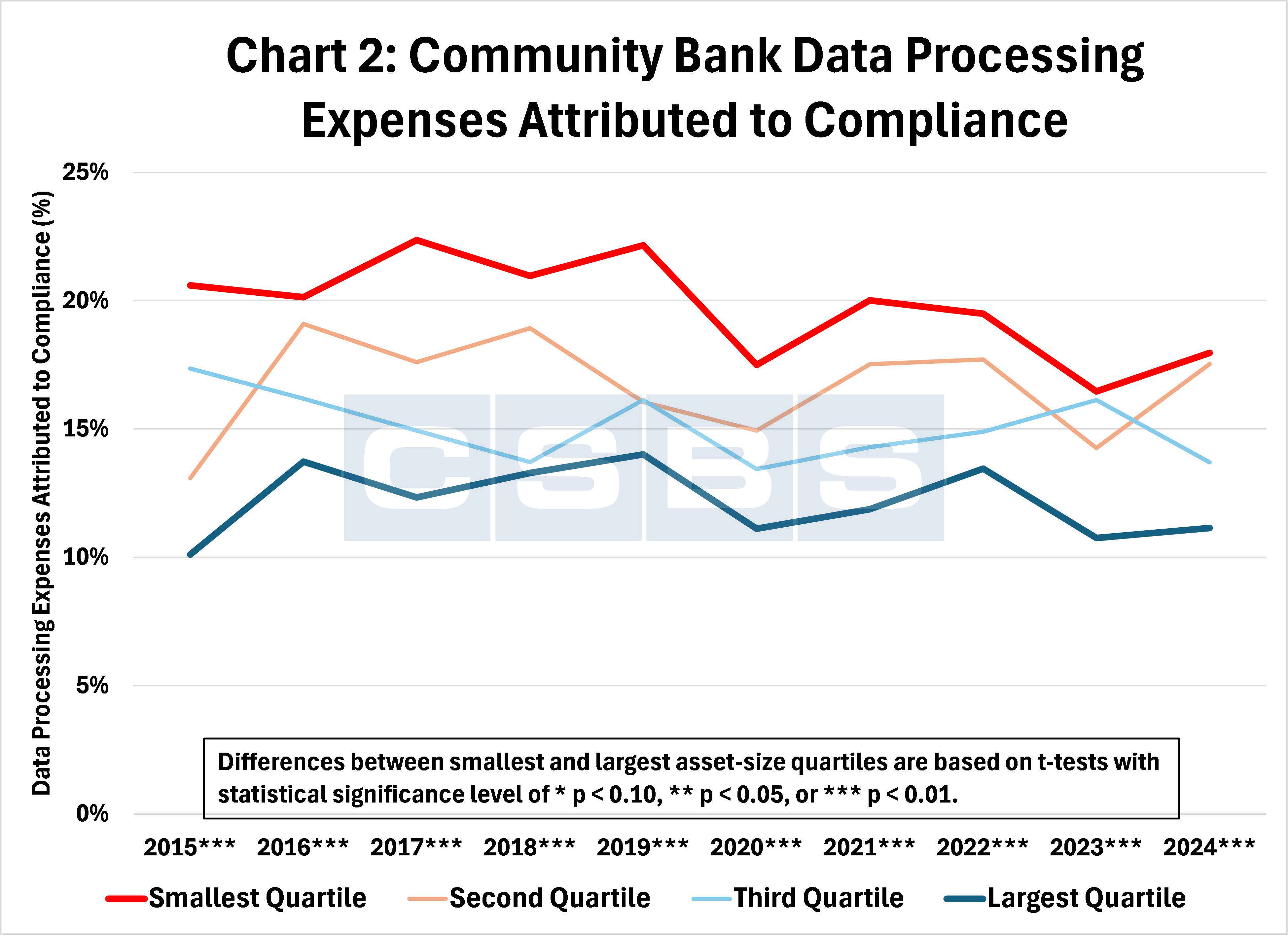

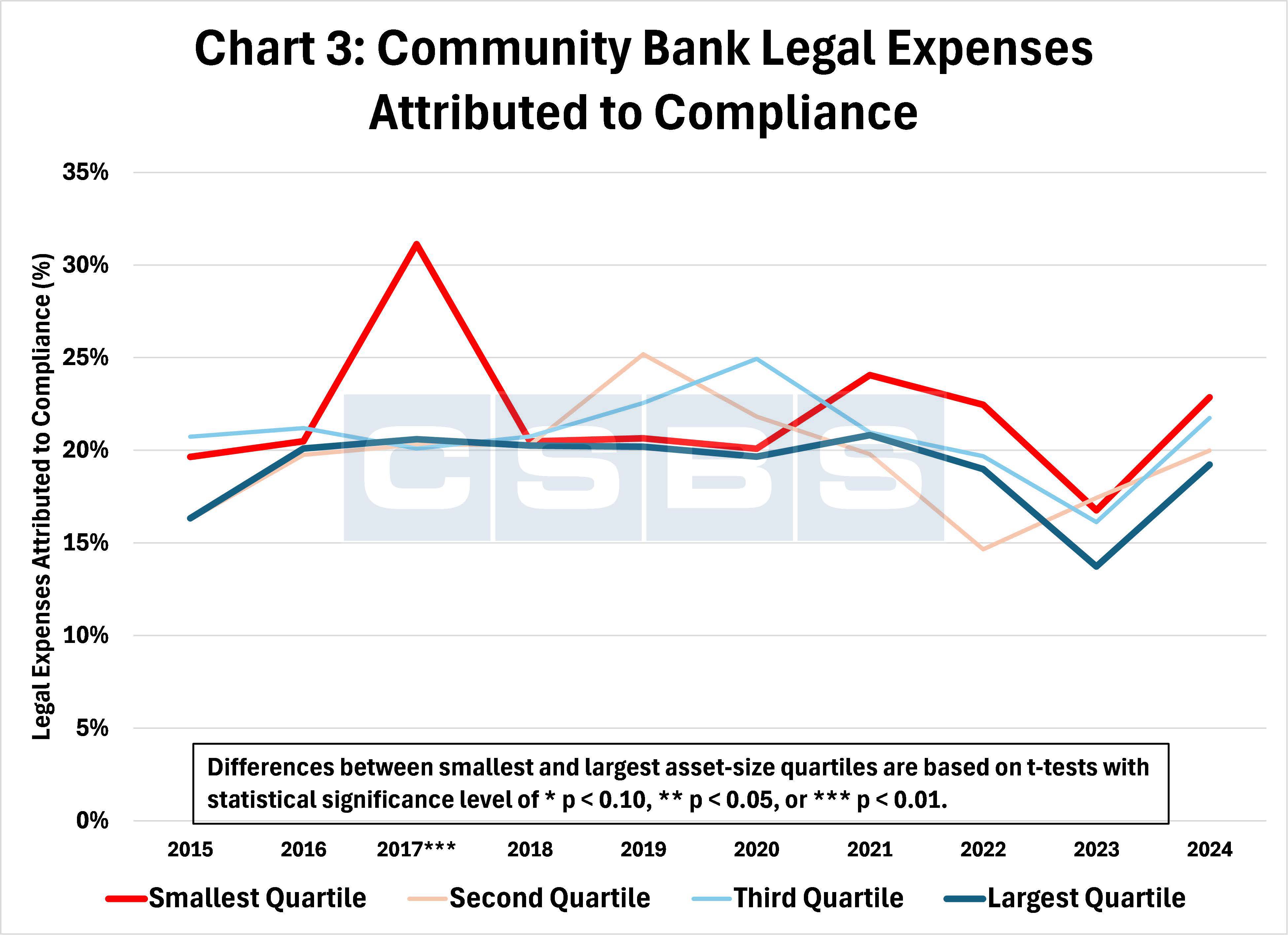

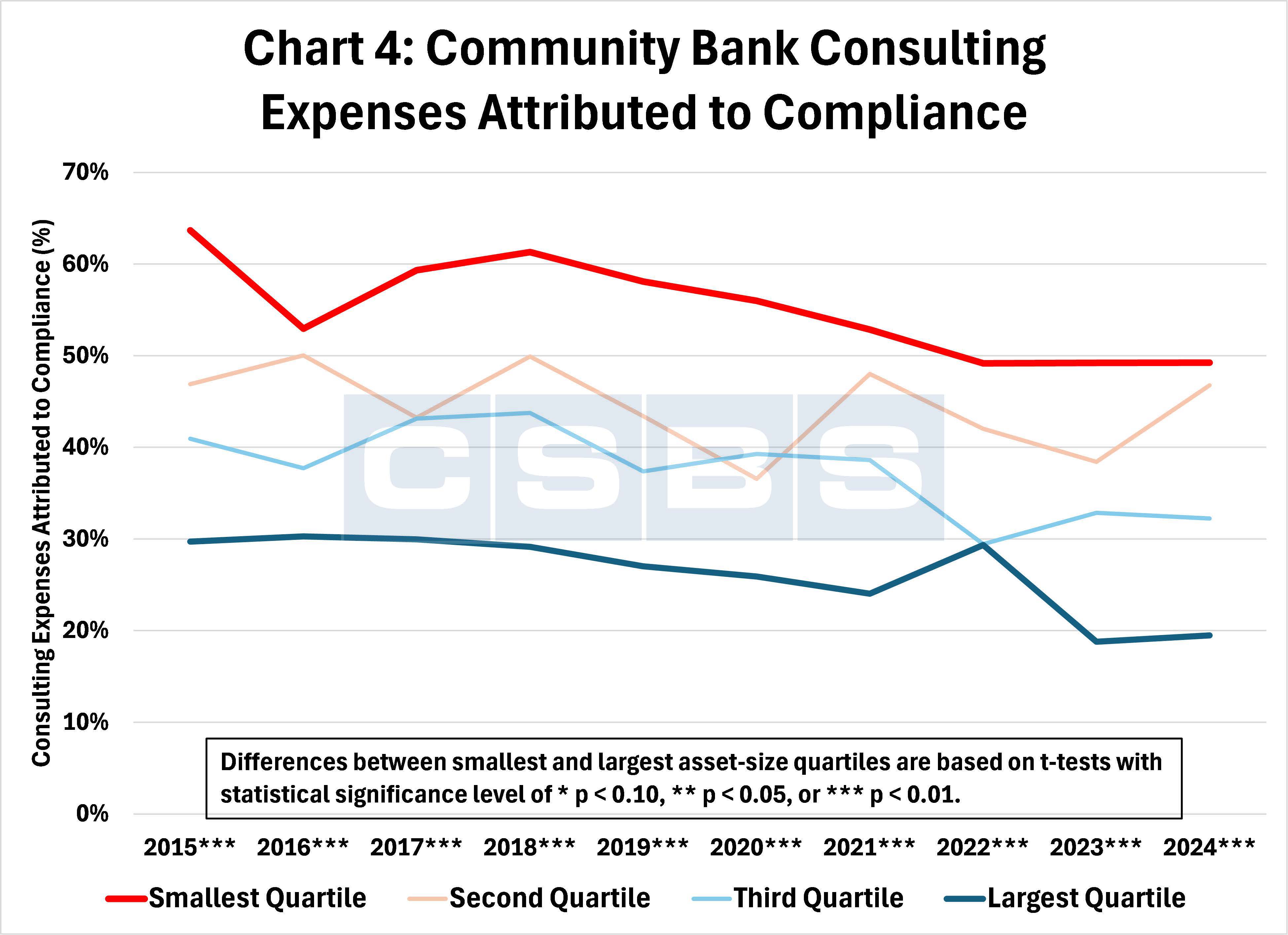

As shown in Chart 1, for personnel costs—the largest overall expense category at most institutions—the smallest banks reported spending roughly 11% to 15.5% of their payroll on compliance tasks, compared with 6% to 10% at the largest institutions—a statistically significant gap every single year. The pattern repeats across other categories. Chart 2 shows that data processing costs consumed 16.5% to 22% of small banks’ budgets versus 10% to 14% for the largest quartile. Accounting and auditing expenses devoted to compliance ran 5 to 17 percentage points higher (see Chart 3). Consulting costs diverged the most, as shown in Chart 4: roughly 50% to 64% for the smallest banks compared with 19% to 30% for the biggest. Only in the legal category did the differences wobble, with smaller banks still spending more—around 17% to 31% versus 14% to 21%—but without consistent statistical significance.

- Chart 1

- Chart 2

- Chart 3

- Chart 4

Why Compliance Costs Hit Small Banks Harder

The evidence puts forth a clear conclusion: regulatory costs behave more like a fixed overhead cost than a variable one, meaning they do not scale down gracefully. The smaller the bank, the bigger the bite.

Why does that matter? Because regulation, though essential to protect markets and consumers, carries real economic trade-offs. Every dollar that goes toward more personnel staff time, paperwork, data systems, and external consultants is a dollar not spent on lending, innovation, or community outreach.

The Post-Crisis Regulatory Environment and Its Impact on Community Banks

These findings fit within a longer-running story – regulatory volume and complexity have increased over decades and accelerated sharply in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Post-crisis changes, whether from the Dodd-Frank Act, Basel III capital rules, or expanded consumer protection oversight, had the cumulative effect of raising regulatory compliance costs. While large banks could absorb those fixed costs, community banks had to spread them across far fewer employees and smaller balance sheets. Many responded by merging or exiting certain lines of business altogether. The number of community banks in the United States has been falling steadily for decades, but the pace of decline accelerated after 2010, and new bank formation has nearly vanished. Regulation is not the only culprit, but these data suggest it is a significant contributor.

What This Study Adds to Existing Research

The detailed working paper reviews the literature on compliance costs and economies of scale in banking. Some earlier studies found hints of the same pattern: fixed reporting and internal-control costs erode small-bank profitability. And others linked rising regulatory complexity to consolidation, arguing that big banks can spread those costs while small ones cannot. What distinguishes this study from earlier research is the use of direct, longitudinal data rather than proxies or simulations. The result is an empirical foundation based on 10 years of survey data as opposed to what had been mostly qualitative arguments.

How Small and Large Community Banks Differ

The working paper also shows how the smallest and largest community banks differ in structure and performance. The smallest quartile of banks tends to carry higher capital ratios—around 12% compared with 10% to 11% for larger peers—signaling conservatism and limited leverage. Yet they also report slightly higher non-performing loan ratios, often 1% versus under 1.5%. Smaller bank portfolios tend to lean heavily toward farm and residential real-estate credit, while larger community banks emphasize commercial real estate and commercial-and-industrial loans. In earnings, the smallest banks generally post lower returns on assets, even though their net interest margins may be marginally higher; compliance costs and limited economies of scale eat into those gains. Funding profiles differ as well: the smallest banks use fewer brokered deposits and less non-core funding, which reduces liquidity risk but constrains growth. None of these characteristics are inherently negative—they reflect mission and market—but together they make smaller banks more sensitive to fixed cost pressures.

Policy Implications: Why Proportional Regulation Matters

The policy implications are significant. If compliance costs are truly regressive—falling hardest on the smallest players—then a one-size-fits-all regulatory regime is both inefficient and harmful to industry dynamism and diversity. Moreover, efforts to “right size” community bank regulation and supervision over recent years may need to be more aggressive going forward. For example, could dramatically simplified or streamlined compliance frameworks, less frequent exams, reduced reporting and documentation requirements, or even wholesale exemptions from certain regulations provide appropriate and meaningful relief for small, low-risk institutions with high levels of capital and limited potential for consumer harm?

Of course, there are some limitations to this analysis. The survey data are self-reported and thus subject to perception bias; what one banker calls “compliance” another might code as “operations.” The methodology shows correlation, not causation; the analysis cannot prove that higher compliance costs cause weaker profitability or slower growth. Nor can it capture differences in internal culture, technology adoption, or market conditions that affect cost structures. But the sheer consistency of the results—spanning 10 years, five expense categories, and thousands of data points—makes the overall pattern difficult to dismiss.

What Policymakers and Bankers Should Take Away

And what ultimately emerges is a portrait of a banking system under strain. Compliance, once a background function, has become a central line item in community bank budgets. The smallest banks devote upward of a fifth of their data-processing and personnel expenses to meeting regulatory expectations—costs that large banks can absorb easier. Over time, that imbalance contributes to consolidation, reduces the diversity of the banking sector, and limits access to credit in small towns and rural areas where community banks are often the only lenders. This research suggests that policymakers must rethink their approach to tailored regulation and supervision: rules that achieve safety and soundness and consumer protection without unintentionally tilting the playing field toward concentration.

So, the takeaway for policymakers is clear: proportionality matters. Regulators can uphold prudential standards and consumer safeguards while recognizing that a small rural bank and a much larger urban bank operate in entirely different universes. Proportional regulation, safe harbors, and support for technology adoption would preserve both stability and diversity. The takeaway for bankers is equally clear: measuring and communicating compliance costs is essential to shaping smart reform. By quantifying the burden with hard data rather than anecdotes, this research gives community bankers and policymakers an empirical foundation for that conversation.

Resilience in the financial system depends not only on well-capitalized large banks but also on the health of the thousands of smaller institutions that finance local businesses, farms, and families. If regulation becomes so costly that it drives those banks from the industry, the result is less competition, fewer choices for consumers, and great systemic fragility. This research illuminates that paradox and points toward a constructive path forward: one where rules are strong but smart, burdens are shared more fairly, and community banks can keep doing what they do best: serving their communities.

- Press Releases

Net Interest Margins Bump Reg Burden as Top Community Bank Concern

Oct 7, 2025

- Blog post

Meet our 2025 Community Bank Case Study Competition Winners

Sep 29, 2025

- Blog post

Meet the 2025 Community Banking Research Conference Emerging Scholars

Sep 23, 2025

Get Updates

Subscribe to CSBS

Stay up to date with the CSBS newsletter