The Critical Role of the Dual-Banking System

CSBS President and CEO Brandon Milhorn

Keynote Remarks

American Bar Association Banking Law Committee

- Watch the Speech

For most of my professional life, I have worked to turn my perspective on law and public policy into executable strategic plans. I like to say that I spent the first 24 years of my life desperately trying to become an attorney, and the rest trying not to practice at all.

For most of my professional life, I have worked to turn my perspective on law and public policy into executable strategic plans. I like to say that I spent the first 24 years of my life desperately trying to become an attorney, and the rest trying not to practice at all.

Then, after a career in national security, I found myself at the FDIC nearly six years ago focusing on financial services, technology, and transformation. How could the agency overcome siloed data, legacy technology, and rigid processes to more effectively supervise banks? How could we rethink our laws, policies, and engagement with industry to foster innovation – reducing costs, improving compliance, and increasing access to financial services for underserved communities?

Over the course of those six years, the FDIC responded to a pandemic and managed several of the largest bank failures in United States history – failures accompanied by bank runs of extraordinary size and velocity. So, after that financial services baptism by fire, I now find myself in front of a room full of banking lawyers, hoping to share my insights on the critical role of the dual-banking system in maintaining a dynamic financial sector in the United States.

The Role of CSBS and State Supervisors

In December, I joined the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS) as president and CEO. Since 1902, CSBS has been the voice of the state supervisory system in Washington. Our members come from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories. They license and regulate the institutions — both bank and nonbank — that provide financial services vital to the national economy.

Our members’ supervisory activities have a uniquely local perspective. State supervisors understand the financial needs of the families and businesses that make up their communities. Our members are focused on consumer protection and safety and soundness, but they also work with their institutions to encourage economic growth and to mature the compliance framework for innovative financial products.

Because of our local perspective, we do not always agree with our federal partners. But that tension . . . and partnership . . . is an integral part of the American economic experiment.

A Uniquely American System

I will not start with Hamilton and Jefferson, but the states have been chartering banks since the early days of the Republic. Congress passed the National Bank Act in 1863,1 forming the foundations of the national bank charter that we know today. Fifty years later, in response to a number of intervening financial crises, Congress established the Federal Reserve System.2 These two laws — the National Bank Act and the Federal Reserve Act — largely set the federal framework for the American dual-banking system. This unique system has sustained the competitive, resilient, and vibrant financial services sector of the United States.

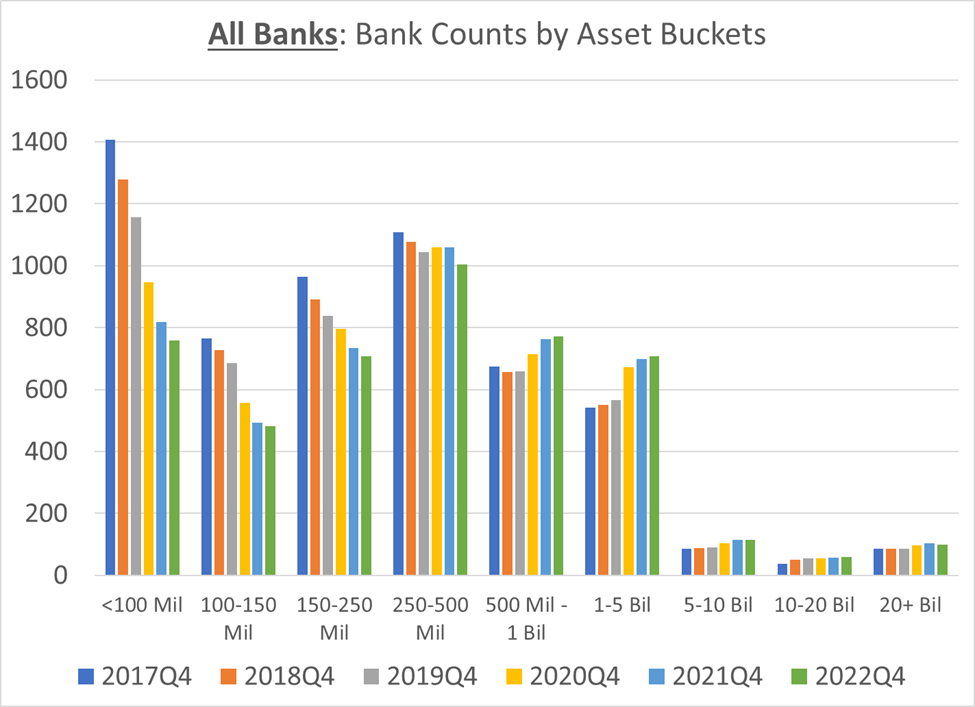

We stand alone among nations in the number and diversity of our banks3 . . . ranging in size and business model from a small community bank operating in one town to some of the world’s largest financial firms operating across the globe.

This diversity is not an accident of history. It is the result of over 200 years of carefully considered and thoroughly debated policy decisions. It is born from our Founders’ commitment to decentralized power and economic self-determination. These core values are reflected in our regulatory system — balancing national interests with local accountability.

This truly American construct allows federal and state governments to focus on their strengths. It balances the stability of a strong national framework with the ability of states to provide for the well-being of their citizens and communities.

Every time the dual-banking system has been challenged, Congress has maintained a state-federal structure of financial oversight — rejecting a single, monolithic approach that would produce myopia and uniformity. Congress has consistently recognized the dual-banking system as a valuable contributor to safety and soundness, consumer protection, and competitive markets.4

Federalization Threatens the Dual-Banking System

In times of stress, however, Washington often forgets the historic success of our diverse and vibrant system. Driven by an instinct to control outcomes, federal regulators attempt to federalize and standardize. Unfortunately, in the wake of last year’s high-profile bank failures, we are seeing the pendulum swing again toward “one-size-fits-all” federal regulatory uniformity.

Our members are concerned with this trend. A federalized approach undermines the tremendous benefits of a financial services marketplace populated by banks of varying sizes and business models.5 While our federal banking laws are grounded in legitimate national interests and priorities, an overly restrictive implementation of those laws can hinder responsible growth, competition, and innovation. A Washington-centric regulatory approach can eliminate the extraordinary economic power of the dual-banking system while providing no . . . or only illusory . . . benefits to financial stability, economic growth, or other national interests.

The Basel III endgame proposal6 is an unfortunate example of the bias federal regulators have towards standardization – and one that will have real-world consequences for credit availability and economic activity.7 Using an already opaque international standard as their starting point, the federal banking agencies have proposed to dramatically increase United States regulatory capital requirements across most financial activities. Despite the mandate in federal law for tailoring regulation to the size, complexity, and risk profile of an institution,8 the proposal also would apply uniform capital requirements across an overly broad range of banks.

The proposed rule offers little to no justification for many poor and exceedingly complex design choices. Take, for example, only one component — the capital treatment of loans to private companies. Under the proposal, these loans would face more punitive capital treatment compared to loans to publicly traded companies.9 There are many reasons that a firm may decide to stay private, and that decision, in and of itself, is not an indication of higher borrowing risk. Not only is there no factual justification for this requirement, but private, mid-sized companies are also important engines of local and regional economies10 — and regional banks

. . . the very banks that would now be covered by the lower thresholds in the proposal11 . . . happen to be critical lenders to these small and midsize companies.12

The proposal also increases risk weights far above the fundamental Basel agreement for numerous products, again with little justification and with seeming disregard for the actual risk of the underlying activity or the economic consequences of the decision.13 If finalized, these choices will have long-term negative impacts for United States financial markets, including a more consolidated and “top heavy” banking sector and reduced competition for certain products as banks reassess profitability.

Capital rules are not the only area where federal agencies are trying to regulate risk out of the banking system. We often hear frustration from our members over centralized decision making from their federal counterparts. The vast majority of supervisory decisions should be made in the field . . . in cooperation with state regulators . . . not from behind a desk in Washington. Sending an issue up the chain to headquarters should be the rare exception, not a standard practice.

This centralized decision making has consequences for institutions and investors. I think everyone in this room would agree that application processing and approvals are historically slow.14 Washington also appears particularly rigid when it comes to diverse or unique business models. Lastly, state regulators know — and I am sure many of those in the room have observed — that the rate of de novo approvals does not match the rate of qualified investor groups seeking a charter.

Preemption also continues to unnecessarily threaten the vibrancy of the dual-banking system. A few weeks ago, CSBS joined with state mortgage regulators to file an amicus brief in Cantero v. Bank of America.15 In Cantero, the Supreme Court will address whether the National Bank Act preempts state laws requiring all banks operating in a state — including national banks — to pay a small amount of interest on residential mortgage escrow accounts.

We may disagree on the merits of requiring some modicum of interest on mortgage escrow accounts, but we should all be concerned about the federal overreach reflected in Cantero. The Supreme Court in Barnett,16 and Congress in the Dodd-Frank Act,17 clearly established the standard that the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) must satisfy to preempt state consumer protection laws. This preemption decision requires a case-by-case analysis, including supporting factual predicates and notice-and-comment.18 Instead, the OCC has avoided the issue for over a decade and pursued “backdoor preemption” by filing amicus briefs in support of national banks. If the OCC can avoid the clear requirements of the law, what stops its intrusion — or the intrusion of other banking agencies — into other areas that are the clear province of the states.

This federal encroachment now extends to the states’ historic responsibility for corporate governance. The FDIC recently proposed19 — with no clear authority — guidelines that purport to strengthen corporate governance of state-chartered banks that are above $10 billion in assets or that are particularly “complex” . . . as determined by the FDIC. Far from best practices, these enforceable guidelines would micromanage how a bank’s board functions, imposing a tangle of organizational requirements and procedural checklists.20 The guidelines would also interfere with the day-to-day operation of banks, confusing the role of management and the board.

In perhaps the most egregious example of overreach — and with no demonstrated basis and without regard to the diversity of state laws on the topic — the guidelines seemingly attempt to establish new federal fiduciary obligations.21 Our members are concerned with this ill-advised proposal that intrudes on over a century of precedent and carefully calibrated duties established in each state — duties that reflect local perspectives regarding the appropriate scope of fiduciary responsibilities.

The FDIC corporate governance proposal also relies on an exceedingly tenuous link to broad safety and soundness authority granted in Section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act.22 The Supreme Court considered arguments this week related to the breadth . . . and continued vitality . . . of Chevron deference.23 It is at least an open question whether the vague authorizations in Section 39 would support the FDIC’s efforts to overturn long-standing state corporate governance rules.24 And, if the Court continues to apply the Major Questions Doctrine to cases with significant economic consequences,25 it seems unlikely that Section 39 contains sufficient Congressional direction to overturn areas of law traditionally reserved to the states.26

There are many lessons to be learned from last year. Both state and federal regulators have taken a hard look at how we regulate and supervise banks, with a renewed focus on core financial risks.27 Unfortunately, in the swath of proposed federal regulations, guidelines, and supervisory actions over the last year, the relationship to the actual causes of the 2023 failures is not always clear. I am concerned that we are asking bankers to prioritize everything, yet focus on nothing, drawing management and board attention away from core financial risks.28

The state-federal balance of the dual-banking system is a feature — not a flaw. Federal regulators cannot alter this balance by fiat. Efforts to “regulate away” risk in banking are a fool’s errand and can threaten the diversity that makes our banks resilient and encourages innovation.

Sustaining the State-Federal Partnership

While we do not always agree, I want to be clear: state regulators are committed to a robust and substantive state-federal partnership. The states charter 79% of the banks in this country, and for every one of those banks, we share supervisory responsibility with our federal partners. Our members work with their federal counterparts daily to keep our regulatory system strong and effective. We also regularly look for ways to improve collaboration.

For example, we have proposed updates to the Bank Service Company Act (BSCA) so that federal regulators have clear authority to share information about banks’ technology providers with appropriate state supervisors.29 Nearly all banks partner with third-party providers, for functions ranging from core processing and lending to deposit-taking and payments. This is especially true for smaller banks. The BSCA authorizes federal regulators to examine these service providers and assess the potential risks they pose to individual client banks and the broader banking system. Thirty-eight states have granted similar authority to their state regulators.

Unfortunately, current law is silent on the ability of federal regulators to share vital information with state supervisors, resulting in duplicative and inefficient oversight of these service providers. The changes we have proposed would codify an important information sharing partnership in federal law. There is more than enough work to go around,30 and we are hopeful that Congress will pass this clarification and make it easier for regulators to protect banks and consumers.

Nonbank Supervision by the States

In Washington, leaders often bemoan a perceived lack of oversight of nonbank financial services.31 These arguments regularly accompany calls for additional federal oversight. Unfortunately, they also typically ignore the fact that states already provide a regulatory and supervisory framework for a large and diverse ecosystem of consumer-facing nonbank financial institutions.

This nonbank regulatory system provides local accountability and operational flexibility as authorized by each state. But, our members also recognize that many financial service providers operate beyond the borders of any one state. These institutions benefit from state-adopted common standards — even when they set the bar higher for safety and soundness and consumer protection. This consistency respects the prerogatives of individual states, reduces compliance costs, and ultimately, increases the availability of responsible financial products.

The establishment of the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System (NMLS) is one example of innovative efforts by the states to provide consistency to the nonbank financial services market. State regulators launched the system in 2008 to license and register mortgage lenders and companies, and Congress mandated the system’s use in the SAFE Act.32

NMLS brought a new level of professionalism to the mortgage industry, and the system continues to be a strong source of consumer protection. Beyond mortgages, NMLS also serves as a platform for licensing debt, consumer finance, and money services businesses. More than 556,000 individuals and nearly 34,000 companies are licensed . . . and supervised . . . through NMLS. Millions of consumers visit NMLS each year to verify the licensing status of a financial services company or professional. The system also provides a mechanism for state regulators to track and manage consumer complaints.

NMLS helped transform state nonbank supervision, and our members are developing other mechanisms to provide shared standards and practices for nonbanks.

Take payments, for example. Working with our members and industry, CSBS helped develop the Money Transmission Modernization Act (MTMA), which increases standards and capital requirements for covered firms.33 Fourteen states have adopted the standards in the past two years, and eight states have introduced the bill so far in 2024.34 This law not only gives certainty to money transmitters, but also to their partners in the financial system. When a bank partners with a state-supervised money transmitter, the MTMA’s high standards allow the bank to conduct more focused due diligence around safety and soundness, consumer protection, and anti-money laundering compliance.

States also approved prudential standards for nonbank mortgage servicers in 2021.35 With these companies serving more and more consumers, states are focused on setting clear expectations on financial condition and corporate governance. So far, six states have adopted these prudential standards.36 Given the multistate operations of most mortgage firms, these six states effectively cover 98% of the nonbank market by loan count and include the 50 largest nonbank mortgage servicers. Our members will expand this coverage as they work with their legislatures or consider other mechanisms to adopt these common-sense requirements.

As you can see, states not only license and supervise a wide range of nonbank financial institutions, but they are also constantly searching for new ways to improve that supervision.

Technology to Advance Supervision

As with nearly all industries, technology has been a driver of change for the financial services sector. Although the core supervisory mission of our members has remained the same, technology has transformed how we execute that mission. NMLS, for example, is not just a licensing system. That platform is also a mechanism for executing our Networked Supervision concept — where nonbank financial institutions operating in more than one state have a single, consolidated, and streamlined exam to support each state’s supervision.37

To advance our efforts to improve supervision, our members have identified three core objectives to build a modern, technology-driven state supervisory system.

First, we are re-imagining supervision so that our understanding of the health of individual institutions and the entire ecosystem can evolve as rapidly as the sector itself. When our supervision cannot keep pace with advances in technology, supervisors become an anchor on innovation across the entire financial system.

Relying on point-in-time exams to supervise a financial system moving at the speed of technology is not a sustainable model. Supervisors need to work with financial institutions to visualize changes over time — at each institution and across the entire ecosystem. This continuous engagement model — supported by advances in supervisory technology — can help identify risks before they threaten institutions, consumers, or broader financial stability.

Second, as financial institutions adopt new technology and develop innovative products and services, supervisors must work with them to mature compliance frameworks. As regulators, it is easy to say, “No!” — standing confidently behind the plate and stridently calling balls and strikes. This mentality, however, does little to guide institutions concerning how their compliance must evolve to incorporate new technologies. And regulation by enforcement or litigation or one-off supervisory action spreads uncertainty across the ecosystem, increasing compliance costs for institutions that are trying to innovate, discouraging new institutions from making the effort, and forcing technology development outside the regulatory perimeter.

State regulators are working with their institutions to mature the regulatory environment. A great example of this public-private partnership can be found in our efforts to promote effective defense against cyber threats.

Working with the Bankers Electronic Crimes Task Force and the United States Secret Service, our members released Ransomware Self-Assessment Tools (R-SAT) for both banks and nonbanks in 2020. R-SAT helps financial institutions assess how they can mitigate ransomware risks and identify other cybersecurity gaps. We recently updated the R-SAT for banks based on real-life lessons learned and insights from cybersecurity experts and financial institutions. This “tools rather than rules” approach is a hallmark of state regulators’ role as both institution supervisor and industry partner.

Finally, an innovative, responsive supervision system will only be successful if it is supported by a talented and empowered workforce. Like every employer in every industry, state regulatory agencies are challenged with hiring and retaining a skilled workforce. To address these challenges, we must re-think how we train our examiners, how we augment our commissioned workforce with subject-matter experts, and how we equip our supervisors with new technologies to visualize and mitigate risks.

Conclusion

Across the nation, our members remain vigilant to protect their consumers and to promote innovation and economic growth in their states. And even when we disagree, we will continue to support engagement and cooperation with our federal partners. After all, this tension — so vital to the American experiment — has made our diverse economy the envy of the world.

Thank you.

Endnotes

Download the Full Speech [PDF]

1 National Bank Act, Ch. 58, 12 Stat. 665 (1863).

2 Federal Reserve Act, Pub. L. No. 63-43, 38 Stat. 251 (1913).

3 See Why America has so many banks, The Economist (May 26, 2023) (“There are more than 4,100 commercial banks in the country, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), compared with 353 in Britain and 261 in Germany.”); see also Stacey Vanek Smith, The U.S. has more banks than anywhere on Earth, NPR, (May 9, 2023) (“The U.S. has more than 4,000 small banks. That’s more than any other country in the world and more than all of the small banks in the entire European Union combined.”).

4 See, e.g., John Ryan, CEO, CSBS, The Bank System We Need, Tenth Annual Community Bankers Symposium (Nov. 7, 2013) (“Offered the opportunity to install a single federal regulator, Congress has declined to do so time and time again: They declined in 1914, when an original goal of the Federal Reserve Act was to create a single, unified federal bank regulator; they declined in 1971, when President Nixon’s Hunt Commission recommended reducing the number of federal banking agencies from five to two, including a federal Administrator of State Banks; they declined in 1984, when President Reagan’s Task Force on Regulation of Financial Services proposed ending the FDIC’s regulatory and supervisory authority; they declined in 1991, when Treasury’s original proposal for FIRREA called for dividing federal bank supervisory authority between the Fed and a new, consolidated Federal Banking Agency; they declined in 2008, when Treasury Secretary Paulson envisioned a new regulatory triumvirate that would have vested all safety-and-soundness supervision in a single agency; and they declined in 2010 when Senate Banking Committee Chairman Dodd proposed several variants of consolidation throughout the course of the Dodd-Frank debate.”).

5 See Appendix.

6 Regulatory Capital Rule: Large Banking Organizations and Banking Organizations with Significant Trading Activity, 88 Fed. Reg. 64028 (Sept. 18, 2023).

7 See CSBS comment letter on Regulatory Capital Rule: Large Banking Organizations and Banking Organizations with Significant Trading Activity (Jan. 16, 2024) (“CSBS comment letter on Regulatory Capital”) (“The proposed changes to credit risk RWA are significant enough that they will undoubtedly impact covered firms’ individual lending and broader business decisions. Indeed, certain covered firms have already signaled that they will ‘de-emphasize lower return portfolios’ in light of the potential revisions and that their ‘RWA management strategy focuses on core clients.’ While each institution will differ in its approach, covered firms will review and analyze each lending area impacted by the proposal in a similar manner.”).

8 See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. 5365(a)(2).

9 See Regulatory Capital Rule, supra note 6, at 64054.

10 See Cecilia Caglio, Matthew Darst, and Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Risk-Taking and Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from Loans to SMEs and Large Firms, Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch. (April 2021) (using the Federal Reserve’s FR Y-14Q dataset of 3,798,946 loan-level observations for 155,589 U.S. corporations to identify nearly 153,000 unique private firms).

11 See CSBS comment letter on Regulatory Capital Rule, supra note 7, at 13-14 (explaining the unjustified increase in funding costs for private companies versus public companies due to a preferable 65% risk weight for publicly traded companies, a feature of Basel III ignored by both the United Kingdom and European Union).

12 See, e.g., Alexandra Scaggs, Small banks, big reach, Financial Times (March 20, 2023) (“Banks with less than $250bn in assets make about 80 per cent of commercial real estate loans, according to economists at Goldman Sachs, along with 60 per cent of residential real estate loans and half of commercial & industrial loans.”).

13 See CSBS comment letter on Regulatory Capital Rule, supra note 7 (outlining several instances of the proposal that deviate from the Basel standards, including i) altered capital treatment of certain single-family mortgages, ii) differing treatment of certain retail lending exposures, iii) rejecting the “simple, transparent and comparable” securitization approach, and iv) flooring the Internal Loss Multiplier at 1 when calculating operational RWA).

14 See Banking Applications Activity Semiannual Report January 1 – June 30, 2023, Federal Reserve Board of Governors (Sept. 2023); see also Jon Hill, Banks’ Wait Time for Fed Deal Blessing Hits Decade High, Law360 (May 24, 2023) (“Notably, the increase in average approval time wasn’t just confined to mergers involving bigger banks. Although the Fed has long been faster to approve merger applications submitted by small banks, which have less than $1 billion in assets, their average wait rose to 72 days last year.”).

15 Brief for Conference of State Bank Supervisors et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners, Cantero v. Bank of America, Inc., (Dec. 15, 2023) (No. 22-529).

16 Barnett Bank, N.A. v. Nelson, 517 U.S. 25, 33, (1996) (“normally Congress would not want States to forbid, or to impair significantly, the exercise of a power that Congress explicitly granted. To say this is not to deprive States of the power to regulate national banks, where . . . doing so does not prevent or significantly interfere with the national bank’s exercise of its powers.” [emphasis added]).

17 12 U.S.C. §25b(b) (“State consumer financial laws are preempted, only if . . . the State consumer financial law prevents or significantly interferes with the exercise by the national bank of its powers….”).

18 Id.

19 Guidelines Establishing Standards for Corporate Governance and Risk Management for Covered Institutions with Total Consolidated Assets of $10 Billion or More, 88 Fed. Reg. 70391 (Oct. 11, 2023).

20 See Statement by Vice Chairman Travis Hill on the Proposed Corporate Governance Expectations for Large and Midsize Banks (Oct. 3, 2023) (“For example, the proposal would require a bank’s leadership to ‘set an appropriate tone,’ ‘develop a written strategic plan,’ ‘articulate an overall mission statement,’ establish a ‘written code of ethics,’ conduct an ‘annual self-assessment,’ and have a ‘comprehensive written statement’ based on its risk profile that should ‘describe a safe and sound risk culture.’ While I appreciate the spirit behind these expectations, I am skeptical that violating any of these requirements should by themselves constitute violations of our safety and soundness standards, and I think our examiners should focus more on banks’ core financial condition rather than micromanaging these types of processes.”); Statement by Jonathan McKernan, Director, FDIC Board of Directors, on the Proposed Guidelines Establishing Standards for Corporate Governance and Risk Management (Oct. 3, 2023) (“While similar to the standards adopted by the OCC . . . [the FDIC] version would tend to undermine accountability for risk ownership, conflate the roles of board and management, preempt state corporate law, and potentially conflict with regulatory expectations applicable to parent companies.”).

21 Guidelines Establishing Standards for Corporate Governance, supra note 19, at 70404 (“The board, in supervising the covered institution, should consider the interests of all its stakeholders, including shareholders, depositors, creditors, customers, regulators, and the public.”).

22 12 U.S.C. 1831p-1.

23 Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

24 The fintech charter proposed by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency had a similarly weak statutory foundation. See CSBS comment letter on Exploring Special Purpose National Bank Charters for Fintech Companies (Jan. 13, 2017); Complaint, Conference of State Bank Supervisors v. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 313 F. Supp. 3d 285 (D.D.C. 2018) (No. 17-0763).

25 West Virginia v. EPA, 142 S. Ct. 2587 (2022).

26 Id. at 2614, citing Util. Air Regulatory Group v. EPA, 573 U.S. 302, 324 (2014) (“[I]n certain extraordinary cases, both separation of powers principles and a practical understanding of legislative intent make us ‘reluctant to read into ambiguous statutory text’ * * * To convince us otherwise, something more than a merely plausible textual basis for the agency action is necessary. The agency instead must point to ‘clear congressional authorization’ for the power it claims.”).

27 See Review of DFP’s Oversight and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, Review of DFPI's Oversight and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank (May 8, 2023); Internal Review of the Supervision and Closure of Signature Bank, New York Department of Financial Services (April 28, 2023).

28 See Michelle W. Bowman, Governor, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, New Year’s Resolutions for Bank Regulatory Policymakers, South Carolina Bankers Association 2024 Community Bankers Conference (Jan. 8, 2024) (“Regulators often identify evolving conditions and emerging risks before they materialize as pronounced stress in the banking system. But too often, regulators fail to take appropriately decisive measures to address them. Regulators can also fall into the trap of getting distracted from core financial risks, and instead focus on issues that are tangential to statutory mandates and critical areas of responsibility. Focusing on risks that pose fewer safety and soundness concerns increases the risk that regulators miss other, more foundational and pressing areas that require more immediate attention.”).

29 The Bank Service Company Examination Coordination Act is a bipartisan, bicameral bill (H.R. 2270 / S. 1230) led by primary sponsors Rep. Roger Williams (R-TX), Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-NY), Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-ND), and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA).

30 See, e.g., The FDIC’s Regional Service Provider Examination Program, AEC Memorandum No. 24-01, FDIC Office of Inspector General (December 2023).

31 See, e.g., Martin J. Gruenberg, FDIC Chairman, Remarks on the Financial Stability Risks of Nonbank Financial Institutions, Exchequer Club (Sept. 20, 2023).

32 Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing (SAFE) Act of 2008, Title V, P.L. 110-289 (July 2008) (codified at 12 U.S.C. §§ 5101–17).

33 CSBS Model Money Transmission Modernization Act (August 2021).

34 As of January 2024, a total of 13 states have adopted MTMA in full: Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia; five states have partially enacted the model law: California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah; Maryland has implemented the MTMA via regulation.

35 CSBS Nonbank Mortgage Servicer Prudential Standards (July 2021).

36 As of January 2024, six states have adopted the CSBS prudential standards for non-bank mortgage servicers: Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Montana, Minnesota, and North Dakota.

37 The State Examination System (SES) — the supervisory component of NMLS — enables multiple states to conduct a single, comprehensive exam of a licensed company. Institutions work with one supervisory point of contact and experience fewer individual exams. In turn, state regulators can deploy supervisory resources more efficiently, access institution-level data from the system, review exams from other state regulators, and ultimately, ensure institutions are meeting supervisory expectations across multiple states. With more than 50 state agencies using the system, supervisory exams using SES are expected to continue to increase.

Appendix

CSBS Data Analytics, Based on Q4 2022 Call Report Data

Get Updates

Subscribe to CSBS

Stay up to date with the CSBS newsletter