Overseeing the Fintech Revolution: Domestic and International Perspectives on Fintech Regulation

Download the Testimony [PDF]

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- State Regulators and Fintech – Understanding the Opportunities and Risks

- Vision 2020 – A Mindset and Roadmap for a Stronger, More Efficient Regulatory System

- Modelling a Commitment to Diversity and Inclusion

- Reimagining Nonbank Licensing and Supervision

- Additional Regulatory Tools

- Strengthening the State System through Industry Engagement

- States Have a Firsthand View of How Technology is Transforming State Regulated Nonbank Industries

- State Perspectives on Federal Fintech Initiatives

- Conclusion

TESTIMONY OF

CHARLES CLARK

DIRECTOR

WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

On behalf of the

CONFERENCE OF STATE BANK SUPERVISORS

On

Overseeing the Fintech Revolution: Domestic and International Perspectives on Fintech Regulation

Before the

TASK FORCE ON FINANCIAL TECHNOLOGY

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

2:00 P.M.

Introduction

Thank you, Chairman Lynch, Ranking Member Hill and distinguished members of the Task Force. My name is Charles Clark. I am the Director of the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions. My department is responsible for the regulation, supervision and examination of Washington’s more than 17,000 state-licensed non-depository entities and more than 90 state-chartered depository institutions, including 38 state-chartered banks. Our department also provides education and outreach to protect consumers from financial fraud.

Today, I represent the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), the nationwide organization of banking regulators from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands. CSBS was established in 1902 to support and improve the dual banking system by bringing state banking regulators together and promoting state-federal regulatory coordination.

State regulators charter and supervise 79% of all U.S. banks and are the primary regulators of a diverse range of nonbank financial services providers, including mortgage lenders, money transmitters and consumer lenders. CSBS, on behalf of state regulators, also operates the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System (NMLS), a licensing regulatory platform for state-licensed nonbank financial services providers in the money services, mortgage, consumer finance and debt industries.

I serve as the chair of the CSBS Non-depository Supervisory Committee, which provides a forum for state financial supervisors to discuss interstate non-depository supervisory matters and is driving several initiatives aimed at ensuring that state supervision of nonbank companies – including many who call themselves “fintechs” – is effective and efficient.

Thank you for holding this hearing on fintech regulation. Nonbank financial services are a large part of the state regulatory ecosystem. As the primary regulator of many nonbank companies who consider themselves fintechs, the state system has expertise, data and real-time supervisory insight into how these companies are interacting with consumers and functioning in the marketplace.

My testimony today will discuss state regulators’ perspectives on the fintech industry and how state regulators have, over the years, approached innovation in financial services. I will detail the following:

- How state regulators, as the primary regulators of a diverse range of nonbank entities, including mortgage lenders, money transmitters and consumer lenders, approach fintech and innovation in financial services.

- How fintechs fit within the context of existing state financial regulatory and consumer protection laws.

- How state regulators are actively involved in ongoing efforts to leverage technology and data as regulatory tools to transform state supervision.

- The impacts of technology on our regulated industries, with a focus on state-licensed money services businesses.

- How state regulators are committed to advancing Vision 2020, a set of initiatives designed to harmonize the multistate licensing and supervision for nonbanks, including fintechs.

State Regulators and Fintech – Understanding the Opportunities and Risks

State regulators are locally accountable, sitting in close proximity to consumers and the communities they are charged with protecting. This perspective makes us uniquely situated to recognize and act upon consumer financial protection issues. When consumers have an issue, they contact us first. Our goal is to help prevent consumer harm before it happens.

Financial regulation and supervision serve as a mechanism for protecting consumers, ensuring financial system stability and assisting law enforcement. The legal framework for state regulation of nonbank financial services industries is activities-based. We have found that the business models of most fintechs can be placed in the context of existing state laws. For example, mortgage and other lending laws apply whether the borrower interaction is online or in person. Likewise, we apply money transmission laws to any company that moves money from Point A to Point B, whether the customer is in person at an agent location or using an app on their phone.

For most fintech products and services, the value added is not product-based, but rather time, ease of use and cost. We can move money across the country or across the globe with a tap of our thumb. It is faster for consumers to fill out an application online, and it is faster for underwriting to be performed using algorithms created to implement credit policies.

When the costs historically associated with financial services are reduced by technology, products can be cheaper and delivery can be faster, but the potential for consumer harm remains – and can be exacerbated by the speed of transactions. As regulators, our job is to see through the shiny stuff to understand the underlying activity and corresponding risks and benefits.

State regulators recognize that the current intersection between financial services and technology has accelerated change in the industry and poses challenges for the state system. We began to address growth in, and the multistate nature of, the fintech industry in December 2013, when the CSBS Board of Directors approved the formation of the CSBS Emerging Payments Task Force. This group of regulators was charged with:

- Serving as the state system’s focal point for fintech developments and issues.

- Evaluating changes in the financial services sector – particularly in payments – and the impact of these developments on state supervision and state law.

- Developing and driving projects and initiatives related to fintech.

At its formation, the task force recognized that external stakeholder engagement was integral to its work. One of the task force’s first initiatives was a public hearing on payments that included testimony from a variety of industry and outside experts. Additionally, during the task force’s first two years, we issued Model Consumer Guidance on Virtual Currencies and Model Regulatory Framework for Virtual Currency, both with public input. In December 2016, the task force changed its name to the Emerging Payments and Innovation Task Force to reflect the task force’s work beyond the payments industry.

To continue the Task Force’s focus on external engagement, in the spring of 2018, CSBS hosted its first ever Fintech Forum. A day-long conference involving regulators, consumer groups and industry focused on discussing fintech business models and their opportunities and risks.

In May 2017, CSBS announced Vision 2020, a commitment to drive towards an integrated, 50-state system of licensing and supervision for nonbanks through a set of initiatives designed to harmonize state regulation, while enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the state system and maintaining strong consumer protections.

Vision 2020 – A Mindset and Roadmap for a Stronger, More Efficient Regulatory System

In recent years, state regulators have broadened the scope of how we work together, especially as we recognize that technology has progressed so quickly, allowing fintech companies to scale rapidly. In 2017, state regulators formally launched Vision 2020, our plan to bring more harmonization into the multistate experience as a means for regulatory efficiency and better supervision. Key to Vision 2020 is preserving the states’ role in protecting the financial system and consumers, while addressing inefficiencies in current licensing and regulatory processes.

Vision 2020 is also a regulatory mindset – a clear vision of how the states are working together to advance nonbank licensing and supervision. It is the states’ commitment to work toward a more consistent, coherent and networked system of state regulation, leveraging technology and data, while reinforcing strong consumer protection regulation and enforcement.

State regulators currently are acting on several Vision 2020 initiatives. Those include:

- Developing robust technology tools that enable regulators to leverage human resources more efficiently.

- Prioritizing IT and cybersecurity training through a sweeping $1.5 million CSBS cybersecurity training program that will train 1,000 examiners in both the bank and nonbank space at no costs to the states by the end of 2019.

- Improving third-party supervision by integrating state regulators into appropriate federal laws such as the Bank Service Company Act.

- Seeking industry input from fintech firms to identify licensing and regulatory challenges and develop actionable responses, while maintaining strong consumer protections and local accountability.

- Formulating a vision and roadmap for implementing regtech solutions that will integrate technology, industry self-assessment and “real-time” supervision to dramatically increase oversight effectiveness while reducing regulatory burden.

I would like to highlight for this Task Force’s attention on element of Vision 2020 – our focus on enabling banks, particularly smaller banks, to leverage innovation responsibly and effectively. To that end, CSBS has been working with Congress for a few years on legislation that would improve bank third-party supervision by integrating the states into the Bank Service Company Act. Members of the Task Force may recall that this Committee unanimously approved the Bank Service Company Coordination Act in the 115th Congress. We urge the Committee to advance H.R. 241, the current version.

Modelling a Commitment to Diversity and Inclusion

In Washington State, Governor Inslee has set a focus on diversity and inclusion, issuing an Executive Order reaffirming our state’s commitment to tolerance, diversity and inclusion. My agency values diversity and inclusion among our staff in carrying out our mission and in all the industries we regulate. I and my entire agency have a responsibility to promote and advocate for a strong and visible culture of diversity and inclusion by creating a welcoming and respectful environment where every person is valued and honored. Additionally, in order to be an advocate for diversity and inclusion with our regulated industries, we have a responsibility to model within our agency that commitment. We have a variety of initiatives aimed at achieving this goal, including:

- Two years ago, we formed a DFI Diversity Advisory Team (DAT) which includes staff from every level of the organization. This group disseminates information promoting diversity and educates staff on diversity topics.

- We have updated our agency policies in areas including harassment prevention, training and developments and hiring to ensure that we are following the most up to date practices in encouraging a respectful and inviting workplace.

- We implemented an intensive training effort on understanding implicit and explicit bias.

Looking at the industries we regulate, we have a variety of structured and informal means for promoting industries and companies that are diverse and welcoming of all individuals.

- My agency participates in our statewide Business Resource Groups – groups of agency staff and external stakeholders with a common interest or characteristic that, among other benefits, bring knowledge and perspectives in areas such as recruitment and retention.

- We participate in a variety of initiatives aimed at improving industry diversity including Women in Banking and Minorities in Banking conference.

- And, we maintain an ongoing dialogue with individual institutions about increasing board and management diversity.

Collectively, we hope that each of these initiatives helps send a message – that DFI is tolerant of all people and supports diversity and inclusivity and that we expect the same of our regulated industries.

Reimagining Nonbank Licensing and Supervision

This section discusses state regulators’ ongoing efforts to leverage technology and data as regulatory tools to transform state supervision.

Regtech for a Stronger and More Networked System of Regulation

For state regulators, regtech is the use of technology to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation. State regulators across multiple states that use the same data points and definitions reduce regulatory burden and improve supervision by harmonizing state-specific requirements, participating in multistate exams and analyzing risk across state lines.

NMLS as a Licensing and Registration System

A critical juncture for state supervision and regtech occurred more than a decade ago, when state regulators recognized growing problems in the mortgage industry as bad actors were taking advantage of a lack of regulatory coordination. Working together, states created uniform mortgage loan originator license application forms in 2006. A year later we began building a common licensing platform to better manage and monitor licensed mortgage lenders, mortgage brokers and individual mortgage loan originators (MLOs) doing business in one or multiple states. That became the Nationwide Mortgage Licensing System, launched in January 2008.

Congress recognized its value and incorporated what is now called the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System (NMLS) in the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008 (the “SAFE Act”). Today, NMLS is a comprehensive system of licensing and registration of all state-licensed mortgage companies and MLOs and for MLOs working in all depository institutions, including banks and credit unions.

In 2012, state regulators began using NMLS to license a broader range of nonbank financial services providers, including money services businesses, consumer finance lenders and debt collectors. Last year, NMLS licensed 24,000 companies. While the majority are mortgage related, about one-third of the companies are from the money services, consumer lending and debt industries.

In addition to serving as a regulatory platform, NMLS has a public facing portal (nmlsconsumeraccess.org) where consumers review individual and company licensing status and publicly available regulatory actions.

Improving Regulation through Data and Analytics

NMLS also supports state efforts to improve regulatory data and information about nonbank financial services providers. States are using this data to understand and evaluate trends and risks in their regulated industries and to better risk-scope licensing and supervisory priorities and activities.

In 2011, we launched the Mortgage Call Report, which is a quarterly report of originations covering more companies than is covered by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. In 2017, we launched a Money Services Business (MSB) Call Report, which is the first and only nationwide report of MSB information especially important in understanding the money transmission industry. These reports create a standardized reporting requirement across all participating states that allow for nationwide trend analysis and risk identification. We are also in the early stages of developing a Consumer Finance Call Report.

The data has given state regulators a deeper perspective into the mortgage industry landscape and has helped us identify applications that might require more scrutiny. As a result, state regulators have become more efficient and more focused on risk. NMLS is useful for federal regulators as well. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) relies on NMLS to register more than 420,000 mortgage loan originators and almost 10,000 banks and credit unions, for example.

SES – The Next Generation of State Licensing Technology

Building on the success of NMLS as a licensing system, the states are developing a new technology platform called the State Examination System (SES) that will integrate with NMLS. This secure, end-to-end technology platform will be the first nationwide system to bring both regulators and companies into the same technology space for examinations. Doing so will foster greater transparency throughout supervisory processes. The system will improve collaboration while reducing redundancy and burden.

Improving Multistate Supervision through Coordination

As the nonbank financial services industry has grown, state regulators have evolved our approach to examining nonbank financial services companies, particularly those that operate in multiple states. In 2008, state mortgage regulators formed the Multistate Mortgage Committee (MMC) to formalize and improve the supervision of mortgage companies that operate in multiple states. This improved the effectiveness and efficiency of state supervision and facilitated the states’ collaboration with federal regulators, including the CFPB. And, it was through the MMC that state regulators helped lead the 2012 National Mortgage Settlement, which provided billions of dollars in relief and restitution to consumers related to the servicing of mortgage loans.

Based on this experience and using the MMC model, in 2014 we formed the Multistate MSB Examination Task Force to coordinate supervision of multistate money services businesses.

Additional Regulatory Tools

A Focus on Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity risk cuts across the full range of state licensed, chartered and regulated institutions. Through industry outreach and coordination, as well as the development of supervisory tools, state regulators – collectively and individually – have been focused on this priority for several years.

As mentioned above, CSBS is in the midst of a massive, far reaching cybersecurity training program for state examiners. In addition, several years ago, CSBS launched an initiative to educate bank executives on cybersecurity through face-to-face dialogue between state regulators and industry, issuance of a resource guide and other information and tools for industry. Through the states’ role on the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), we participated in the development and deployment of the FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool for banks.

Enforcement

Our interaction with industry covers a continuum – including enforcement as a key tool regulators use to carry out our responsibilities. Just as our regulatory regimes are activities- based, our approach to enforcement is activities-based. Since January 2017, 69 individual enforcement actions at money transmitters have been uploaded to NMLS.

Most recently, state regulators devoted significant resources to a multi-state examination addressing the massive data breach Equifax experienced in 2017. Last year, eight states took action against Equifax, requiring the company to take various actions to improve risk management and information security.

Strengthening the State System through Industry Engagement

As a part of Vision 2020, CSBS formed a Fintech Industry Advisory Panel (FIAP). Through an open and transparent process, CSBS sought FIAP members willing to commit to focused work on identifying the challenges of a 50-state system and to offer concrete solutions. The panel ultimately had 33 fintech firms representing both the payments and lending industries. After more than 100 hours of meetings, the FIAP made a series of recommendations to the CSBS board in December 2018. CSBS announced its plans to move forward with 14 of the recommendations in February 2019. A summary of the FIAP recommendations and next steps is included as an appendix to my testimony. Key among these efforts:

- Develop a Model State Payments Law. We currently are developing a model state law for money transmitters with uniform, risk-based requirements. Though each state generally uses the same framework for money transmission laws, each statute has its own unique definitions and requirements for money transfers. States also might interpret and implement laws differently, even when the statutory language is the same. A model law will enable money transmitters to build national scale more easily, improve state supervision and ensure consumer protections.

- Rationalize Multistate Exams. Through the One Company, One Exam pilot, a nationally operating money transmitter – instead of undergoing multiple state examinations – will be examined only once in 2019 in a manner that meets the supervisory needs of many states. The process incorporates the requirements of multiple states into one exam and will identify areas where increased communication and advanced information sharing will improve state efficiency and significantly reduce burden for firms. The program will help states improve their processes – a crucial element of states protecting consumers while promoting national business models – and will inform the continued development and future deployment of SES. Building on the one company/one exam pilot in 2019, we are working on a three-year national examination schedule for larger MSBs in which states will conduct joint examinations staggered with offsite examinations and reliance by non-examining states on the results of the joint reviews. Once established, this national schedule will be real and substantive coordination that will improve oversight and significantly reduce regulatory burden.

- Streamline Multistate MSB Licensing. My agency, the Washington Department of Financial Institutions, devised and has been leading this effort, which the CSBS board last month agreed to make a CSBS initiative. To date, 23 states have signed on to the MSB licensing initiative, which is intended to curb duplications in the licensing process. If one of these signatory states reviews key elements of state licensing for a money transmitter, other participating states agree to accept the findings. By utilizing NMLS, applicants now have a process for submitting most license application materials only once instead of submitting them separately to each participating state. For licensing requirements that are common among the states, the applicant will also have a single point of contact with the state selected to review the common licensing requirements.

- Develop Tools for Navigating the State System. The FIAP urged the states to provide more tools to help companies better understand licensing and regulatory requirements as well as more easily navigate the licensing process. Two tools are now in development: an online repository of state licensing guidance, which will be available on csbs.org, and a license wizard, which will enable applicants to quickly identify licensing options based on their business model. Related to these tools, we are committed to continuing to build stakeholder understanding of the growing nonbank industry. CSBS is in the process of publishing a series that looks at how the nonbank financial services industry is currently supervised and ways to enhance supervisory approaches. In early June, we published our first chapter, “Introduction to the Nonbank Industry,” which provides an overview of market segments within the nonbank industry.

States Have a Firsthand View of How Technology is Transforming State Regulated Nonbank Industries

The convergence of innovation and financial services has affected every industry within the state regulatory portfolio. Data from NMLS has helped state regulators understand these changes and spot trends. This section spotlights trends in two major areas of state nonbank regulation: the nonbank mortgage industry and state-licensed money services business.

Technology, including Regtech, has Driven Expansion and Growth in the Mortgage Industry

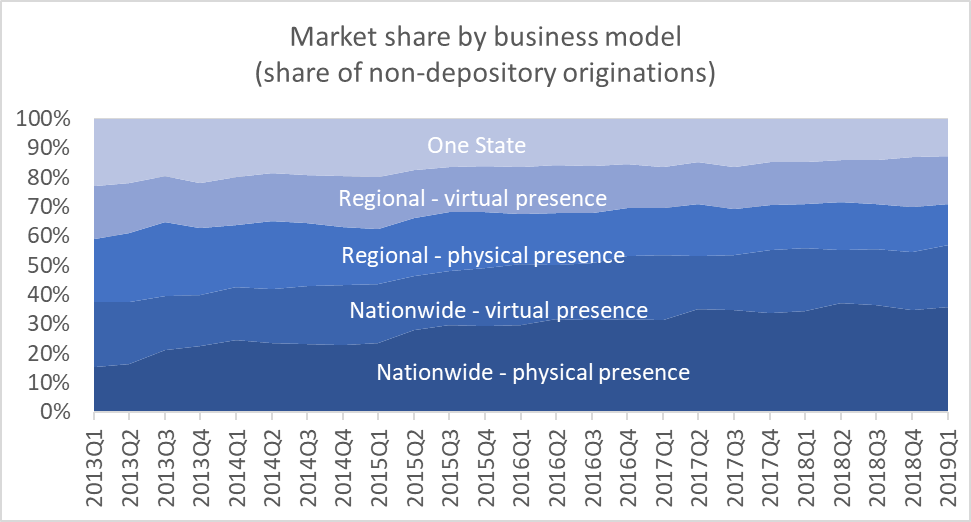

Using NMLS data, we analyze mortgage company business models based on two main criteria: regional vs. nationwide and physical vs. virtual presence. We consider a company to be nationwide if it has a license in at least half of the states. A company has a virtual presence if it has fewer branches than state licenses and therefore does not maintain a physical presence in every state where it does business.

One change brought about by technology is the increase in the number of firms operating nationwide, as technology helps companies reach customers and NMLS has helped bring uniformity to state licensing. The number of nationwide companies with a physical presence has approximately doubled over the past six years, as has the number of nationwide companies with a virtual presence. Similarly, the nationwide companies have won market share from regional companies in mortgage originations.

The number of mortgage loan originators employed by nationwide companies with a physical presence has nearly doubled over the past four years, while the number of MLOs employed by other business models has remained steadier. On the other hand, the average number of licenses per MLO has nearly doubled for nationwide companies with a virtual presence, while remaining steady for other types of mortgage companies.

These two trends show that companies using technology to reach customers, including fintechs, are acquiring more licenses for their MLOs, thereby growing their virtual presence (via phone or technology). Meanwhile, nationwide branch-heavy companies are growing their actual MLO population.

The Evolution of the State-Regulated Payments Industry

Many early fintechs came from the money transmitter space, leveraging technology to create new business models, new delivery channels, automated decisions and partnerships with traditional banks. Moving money across continents and across oceans inherently requires technological innovation. While MSBs are at the cutting edge of technology today, their history of deploying advanced technology goes far back in time to the telegraph and international undersea cables for transmission of money.

Technology-Driven Changes to the MSB Industry

The states have held exclusive jurisdiction over MSBs for over 100 years. State supervision of MSBs began at the turn of the 20th century when states began protecting their residents’ funds as immigrant populations sent money by steamship back to Europe and Asia. The earliest state money transmitter laws date back to 19071.

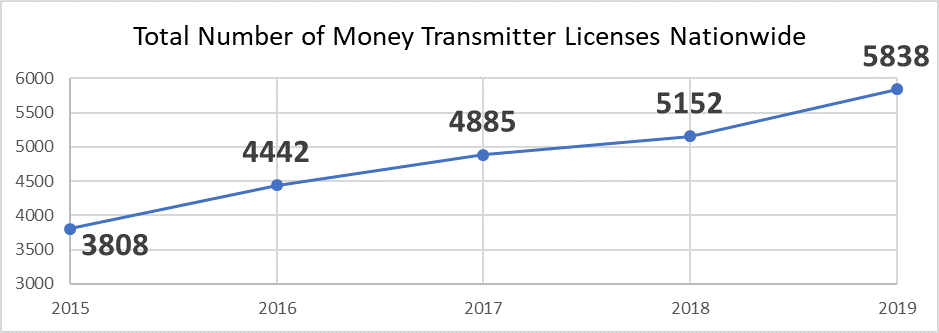

In recent years, technology has driven changes and growth in the MSB industry, as seen in the chart below.

This growth represents an increase of 53% over five years. While the number of licenses has increased, NMLS data show that the number of companies at any given time has been relatively stable. Therefore, the increase in the number of licenses means that existing companies are expanding their geographic footprints by obtaining licenses in more states. This is reflected in both the growth of multistate money transmitters (18% growth) and the average licenses per company (55% growth), as shown in the following chart.

| 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multistate Money Transmitters | 272 | 250 | 245 | 243 | 231 |

| Average Licenses per Company | 11.5 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 7.4 |

This licensing data signal two trends. First, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) have played a significant role in the industry. As startups grow, they are being bought by larger, established companies. Second, companies frequently undergo orderly wind-downs, change business plans to activities that do not require a license, or roll up multiple subsidiaries into one license. Perhaps most regrettably, several companies have been de-risked, a trend that has slowed but still affects the industry.

The State System of MSB Supervision

Altogether, from May 31, 2014, to May 31, 2018, NMLS data show a total of 173 companies exited the licensed money transmission space. A similar number of companies became licensed over the same time period. Because state laws are designed to protect consumers while companies try and sometimes fail, these numbers reflect a state system that works. Policymakers do not hear about money transmitter failures because state safety and soundness requirements protect both the taxpayer and the consumer from risk of loss.

Case in point: during an examination that involved coordination with the Brazilian Central Bank and two private Brazilian banks, it was determined that a licensed money transmitter was using falsified records, evidencing an even broader pattern of illegal activity. As a result, the states coordinated on enforcement, stopping the company from accepting and transmitting money across 37-states.2 All consumers who lost money were made whole, even without deposit insurance.

Since 2015, the average state has seen a 68% increase in licensees, from 69 licenses to 116 licenses. The state-by-state licensing increase reflects the geographic expansion of a handful of very large companies that now dominate the market. As of Q1 2019, a total of 71 companies are licensed in 40 or more states, compared to just 37 companies in 2015—an increase of 92%. These 71 companies are responsible for 80% of the $1.39 trillion transacted in the United States in 2018. The six very largest companies were alone responsible for 66% of all funds transferred or stored, moving more than $900 billion in 2018.

While states have exclusive jurisdiction within their borders, the money transmission business is national – and often global – in nature. As the industry has evolved, so too have state regulators to create a more networked “state system” utilizing collective resources on a national basis.

The MSB Call Report, launched in 2017, collects quarterly activity and financial data from MSB companies, including nationwide totals for money transmission, stored value, payment instruments and virtual currency transactions. In addition to information about the size of the MSB market, the MSB Call Report provides a picture of industry composition.

Year end 2018 MSB Call Report data show that six companies moved 66% of the funds transferred or stored by all MSBs. Three of these companies are licensed in every state, one is licensed in 49 states and the last is a crypto company licensed in 42 states. These companies are not alone – 69 companies are licensed in 42 or more states.

Despite the market dominance of these few companies, the majority of MSB companies are licensed in only one state. These small licensees take on many different roles in state economies, including payment services in local stores, startups and remittance providers for local ex-pat populations. Given this high level of competition, it is no surprise that 173 companies ceased licensed operations over a five-year span.

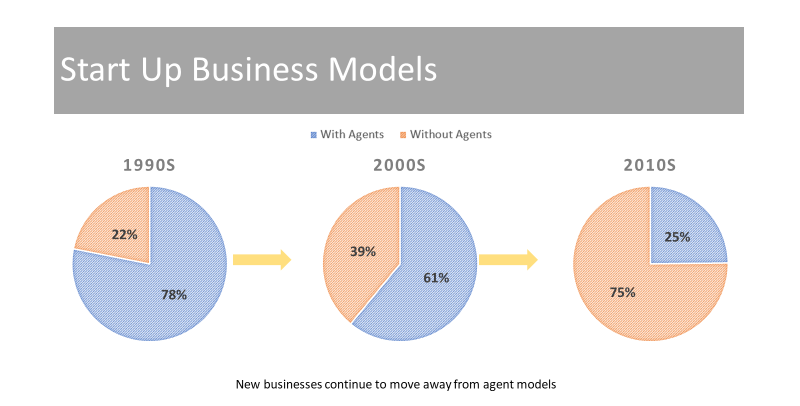

A dynamic shift has occurred in the money transmission industry over the past decade. Of the 64 currently operating licensees that were formed in the 1990s, 78% utilize an agent-based business model, where people handle the transaction from physical locations. Since 2010, conversely, 75% of the 133 newly formed companies utilize a business model without agents but facilitated by online technology.

Using this data, state regulators developed a means of identifying MSBs that could be identified as “fintech” companies. If a company has two or fewer agents and is operating in four or more states, the best logical conclusion is the company is utilizing the internet for its operations. These companies collectively accounted for more than 55% of all transaction volume in 2018.

| Sector | Sector Total | Fintech Total | Fintech Market Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| Money Transmission | $831.5 billion | $448,131,604,535 | 54% |

| Payment Instruments | $175.2 billion | $3,500,525,533 | 1.9% |

| Stored Value | $294.9 billion | $254,356,621,671 | 86% |

| Check Cashing | $14.1 billion | $0 | 0% |

| Currency Exchange | $5.4 billion | $469,040,022 | 9% |

| Virtual Currency | $69.5 billion | $64,649,566,505 | 93% |

| Total | $1.39 Trillion | $771,101,358,266 | 55.5% |

Importantly, this fintech market share has grown since 2017, with money transmission leading the way from a volume perspective and virtual currency leading the pack in overall growth.

State Perspectives on Federal Fintech Initiatives

State Regulators and the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Innovation Report

The U.S. Department of Treasury recognized the importance of harmonizing state financial regulation and the progress state regulators have made in its July 2018 report: Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation.

In the report, Treasury voiced support for state regulators’ efforts to build a more unified licensing regime and supervisory process across the states and floats that such efforts might include adoption of a passporting regime for licensure. State regulators are already engaged in implementing several of the recommendations, which include drafting a model law, using NMLS to foster a more cooperative approach among state regulators in the supervision of nonbank financial services companies and streamlining examinations.

Importantly, the report recognized Vision 2020 as a response to the state regulatory challenges raised by the nonbank financial services industry and encouraged states to continue our focused effort to implement a variety of Vision 2020 initiatives.

“It is important that state regulators strive to achieve greater harmonization, including considering drafting of model laws that could be uniformly adopted for financial services companies currently challenged by varying licensing requirements of each state. Treasury encourages efforts to streamline and coordinate examinations and to encourage, where possible, regulators to conduct joint examinations of individual firms. Treasury supports Vision 2020, an effort by the Conference of State Bank Supervisors that includes establishing a Fintech Industry Advisory Panel to help improve state regulation, harmonizing multi-state supervisory processes, and redesigning the successful Nationwide Multistate Licensing System .”

State Regulators’ Concerns with the OCC’s Proposed “Fintech” Charter

There is one aspect of the Treasury report we particularly disagree with, however. It supports the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s (OCC) decision to accept applications for special purpose national bank charters from nonbank fintech companies that do not and would not engage in receiving deposits or be insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. We strongly oppose the OCC’s decision and have filed litigation against it.

Our reasons are clear. First, The OCC does not have the statutory authority to issue federal banking charters to nonbanks. Only Congress can make such a decision, especially as the charter creates public policy implications that must be debated in Congress. Second, a federal fintech charter would disrupt the market by picking winners and creating losers, drawing a handful of large, established entities and give them a competitive advantage over new market entrants that have historically injected innovation into our financial system. Third, a federal fintech charter would preempt important state consumer protections. Fourth, such a charter would harm taxpayers by exposing them to the risk of fintech failures.

Conclusion

As the primary supervisors of nonbank financial providers, state regulators appreciate the commitment of both this Task Force and the Committee to ensuring effective supervision of financial technology companies.

As I have outlined, state regulators are engaged and proactive in ensuring that state supervision of fintechs is effective and efficient in this rapidly growing space. State regulators oversee a diverse ecosystem of bank and nonbank entities, including mortgage lenders, money transmitters and consumer lenders. State regulators are committed to using technology and data to make the states more effective as regulators by advancing toward a regulatory system that spots trends early, prioritizes resources to address risks and supports the emergence of pro-consumer innovation.

1. See Immigrant Banks, Reports of the Immigration Commission, p. 318, (Dec. 5, 1910).

2. See, e.g. Braz Transfers Cease and Desist Order.

Get Updates

Subscribe to CSBS

Stay up to date with the CSBS newsletter